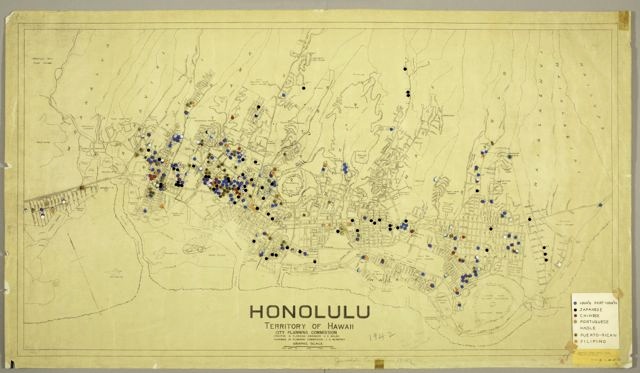

Map Location: Drawer 6, No. 29b

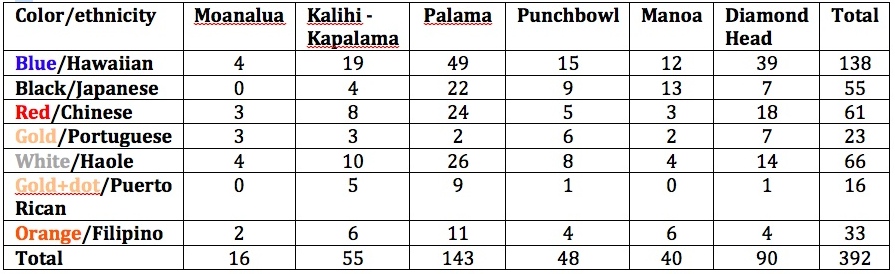

This map illustrates juvenile crimes that found their way to the courts in 1942, the first year of direct US involvement in World War II. Likely done in 1943 or later when statistics from 1942 were available, the map’s focus is the ethnicities and residences of juveniles in the Honolulu area. The following table contains a rough count of the map’s dots.

No specific paper has claimed this map. However, its presence in the Collection isn’t unexpected since RASRL writers frequently wrote about juvenile delinquency. Contemporaneous with this map is a study by B.B., “Juvenile Delinquency in Honolulu during the War” (RASRL Student Papers, Box A-1).

B.B. detailed her sources and explained her process. She read other RASRL writers’ papers on slums, prostitution, family disorganization, and delinquency available in the Sociology Lab’s collection. She looked at newspaper accounts about juvenile crimes occurring in other cities. In Honolulu, she met with juvenile court staff; a Mrs. Taylor of the Susannah Wesley Home; Cenie Hornung, UH’s Counselor of Women; and La Verne Bennett, advisor to UH’s Women’s Athletic Association (Ka Palapala, 1943).

The writer talked to various “types of people”: a friend who was a lei seller; UH students; and teachers at Mid-Pacific Institute and Roosevelt High, Kalakaua Intermediate, and Punahou schools. She interviewed social work students and practicing social workers, a Lt. JG in the Navy, people who worked in “downtown business concerns,” and high school friends. She spoke with policemen and gathered information from staff at Child and Family Services, the Psychological Clinic, Queen’s Hospital, Pālama Settlement, and Clorinda Low Lucas of Hawaii’s Department of Public Welfare.

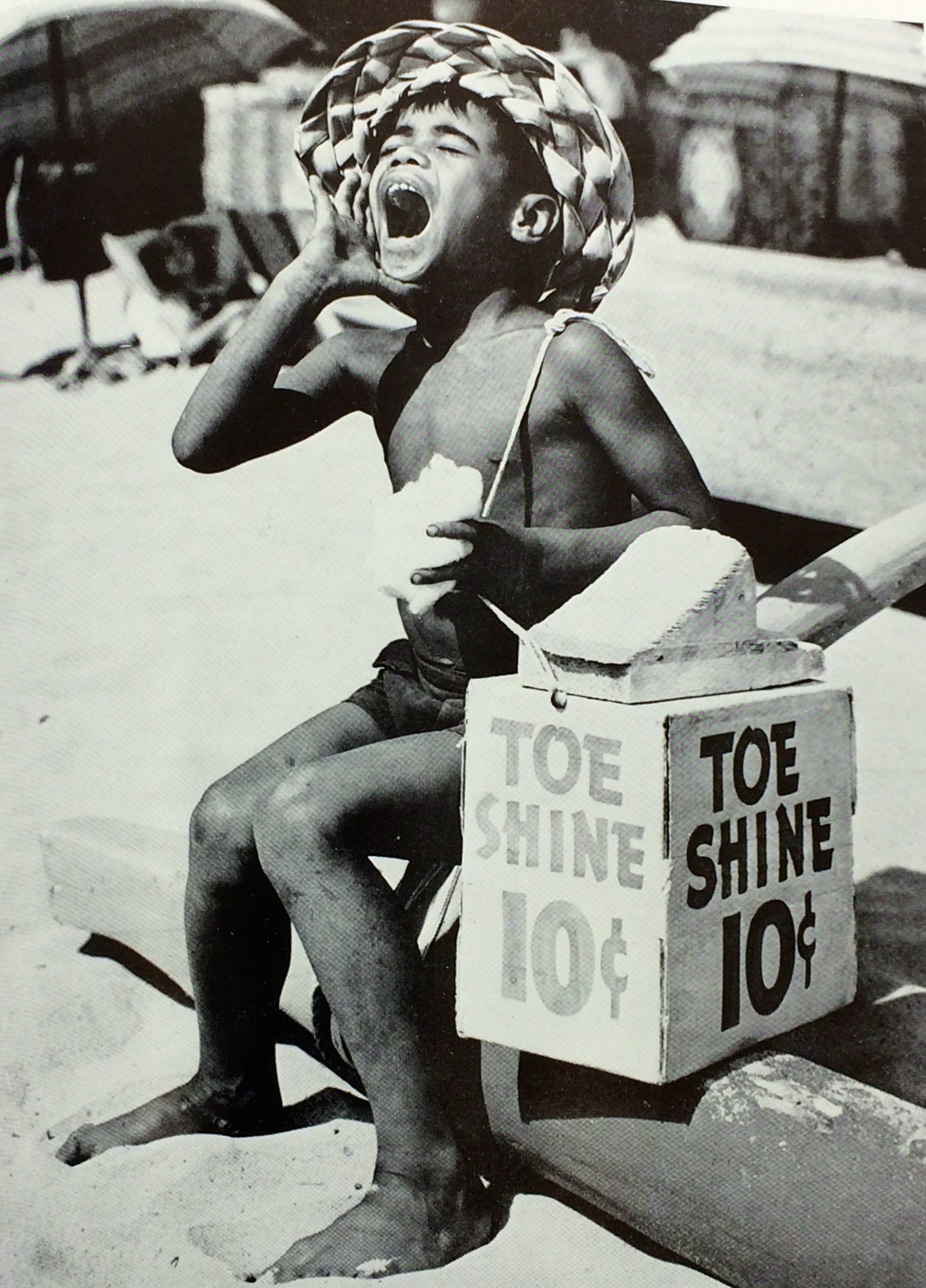

The writer shares what she heard in a lecture given by Sgt. Nobriga of the Honolulu Police Shoe Shine Club, an organization created to provide wholesome activities for shoeshine boys. Nobriga said this club included about “500 boot blacks” shortly after the Club had been organized and five months later, had grown to about 1,500 members.

Sergeant Nobriga told the Sociology class that he gave a big picnic at Palama field for the club. Nearly all the boys signed up to come. But on the day of the picnic only about three hundred boys came. Nobriga became curious and went down town to investigate. He found boys on the streets shining shoes. “Why aren’t you at the picnic?” he asked. “Because while the other boys are at the picnic, now is a good time to do business,” was the answer he got.

B.B. summed up things this way:

War times are abnormal times . . . There is easy money, school is sometimes sketchy. Parents and teachers are tired. Discipline is lax. Older friends quit school and work. They sport flashy clothes, bulging wallets and sometimes their own cars. . . . After hearing his older brothers scoff at school, [a boy] is likely to think school is rather useless too. When money is so much in evidence he very likely would want lots of his own money too and would cast around to see how he could get some. Shining shoes and selling papers is work but it brings money. Near military projects gambling is popular and doesn’t need much effort. Girls want to get easy money too and if parents haven’t taken much care, and the girls are not positive as to what is right or wrong, they can easily be tempted into the “ancient profession. . . .”

Occasionally RASRL writers referred to what they’d seen in Paradise of the Pacific. The intent of this publication, commissioned by King Kalākaua under royal charter in 1888, was to promote business growth and tourism (and occasionally exhort Haole to settle in Hawai‘i) by assuring citizens of the United States that the Islands were civilized. Paradise offered an interesting mixed message, most vividly seen in its rich collection of photographs: Hawai‘i as a bustling paradise for capitalists and Christians and an exotic and sensual one for tourists. But after the attack on Pearl Harbor, leisure travel to Hawai‘i became virtually impossible and the only visitors arriving were troops and defense workers. In late 1942, Paradise’s new editor Eileen McCann O’Brien shifted the magazine’s focus to the social and economic effects of the war (Bob Dye, ed., Hawai‘i Chronicles III: World War II in Hawai‘i from the Paradise of the Pacific, p. 8).

In the May 1943 issue, F. Deal Crooker, educator, and W. Harold Loper, a supervising principal in the Territory, authored “Honolulu Attacks a Challenging Problem.” The problem being attacked was juvenile delinquency and the army with which to attack it was the newly-formed but not yet active General Education Council comprising “citizens representing service clubs, social agencies, schools, homes, employers, motion picture houses, radio broadcasting companies, magazine distributors, etc., etc., coming together monthly to hear reports of subcommittees appointed to investigate various aspects of the general problem” (p. 32).

By 1944, circulation of Paradise of the Pacific was up in large part due to the magazine’s popularity with military personnel and civilians from the continent stationed in Hawai‘i. During this period, there were nearly 859,000 people in Hawai‘i with about 407,000 in the military (Dye, p. 9). It’s not known whether local people were avid Paradise readers, since the publication clearly catered to Haole: its intent was to portray Hawai‘i as worthy of statehood and its tone was one of insider information offered by Haole kama‘āina to newcomers.

As mentioned previously, RASRL writers had access to fellow sociology students’ papers. The 1942 and 1943 “morale diaries,” which were coded to protect the writers’ anonymity, were sometimes read aloud in sociology classes. In these diaries RASRL writers shared conversations, their own as well as ones overheard, provided eyewitness accounts of incidents, passed on others’ accounts, and freely shared rumors. Juvenile delinquency occasionally was the topic:

My brother (17 years) comes into contact with a crowd of young hoodlums (Hawaiian, part-Hawaiian, and Orientals). He reports this interesting aspect on service men vs. Honolulu youths’ “fights.” The Honolulu police are apparently getting “fed up” with the numerous battles. Since they cannot arrest service men (the M.P.’s and S.P.’s are supposed to be called), they really “get hard” with the island boys. They take them down to the station and beat them “only on the stomach – they punch them” so that no bruises will show (UHSj-440-I, Student Journals, Folder 15, 12/17/43).

One writer felt that the closing of Japanese language schools would be the first step toward delinquency, since the boys were free to hang out in the afternoons with their gangs (UHSj-380-I, “The Effect of War on Family Relations,” Student Journals, Folder 11, 5/43).

One morale diarist, as adviser to the Girl Reserves at Roosevelt High School, attended a lecture with her girls given by a policewoman from the Crime Prevention Bureau. The topic was juvenile delinquency with a special emphasis on the “soldier-girl relationship.”

According to [the policewoman], “the problem is getting worse each time and the offenses on the part of the girls are increasing faster than that of the young boys.” She explained that her duty as a policewoman was to pick up girls who were in trouble and to investigate cases involving missing girls. She also said that parents sometimes come to the bureau with their daughters to discuss problems concerning behavior of the girls (UHSj-442b-I, Student Journals, Folder 15, 5/25/44).

The policewoman also mentioned a film about juvenile delinquency – its causes and remedies – that had recently been shown at McKinley High School. It’s possible that the film she referred to was As the Twig is Bent (1943).

No morale diary was without first-hand accounts of what was happening on Honolulu’s buses. During the war, buses were nearly always packed, and everyone – regardless of ethnicity, age, social class, occupation – was on board. One morale writer submitted a more formal paper about the bus system. In it she cited an unnamed article in the July 1943 Paradise of the Pacific that demonstrated the huge increase in ridership. In November 1941, the average number of bus passengers was 125,484 per day; by November 1942 the number had gone up to 320,228 (UHSj-436b-I, “Effects of the War on the Bus Situation,” Student Journals, Folder 14, Spring 1943).

This writer said the reasons for the increase were the rationing of gas, the mass migration to Hawai‘i of defense workers and servicemen, and the decrease of home delivery service by stores and markets. Honolulu Rapid Transit (HRT) faced its own set of challenges: the need to add new bus routes as war workers began moving into formerly more sparsely populated areas and to hire new drivers since many experienced ones had left for better paying defense jobs. Because HRT didn’t have enough buses, the city had to lease some from the US Navy.

This same RASRL writer learned this from her interview with an HRT bus driver:

There are some local boys, a big gang . . . They ride the bus during the night with the intention of looking for trouble. I don’t know why, but these boys seem to have it in for the servicemen. They don’t like them and they told us that anytime we need help just call on them. They’re a rough bunch, but in a way it’s good to have them on the bus when driving toward the airport. They sort of protect us, especially small guys like me (UHSj-436b-I).

Buses regularly were the site of clashes between locals and outsiders, among ethnic and racial groups, between the drunk and the sober. Many writers heard about incidents second- or third-hand and included them in their diaries. Several morale diarists related the following incident where WACs stood on the bus while Chinese-Hawaiian girls were seated:

“If we were on the mainland, the dark people usually stood up for the white people.” As soon as these words were spoken, one of the three Chinese-Hawaiian girls stood up and slapped the WAC to the floor. Everybody in the bus was astounded. The WAC picked herself up from the floor and said, “I wasn’t talking to you.” The Chinese-Hawaiian girl answered, “But it was meant for us.” Then another girl of the three Chinese-Hawaiian girls stood up to offer her seat to the WAC, but she refused (HSj-320a-I, Student Journals, Folder 8, 4/25/44).

Although likely apocryphal, this story rings true. While statistically girls were not being charged with aggressive acts, they were out and about in Honolulu, on the streets, in movie theaters, passing themselves off as adults in bars and clubs, hanging on the arms of servicemen and defense workers, and like everyone else, riding the buses where just about anything might happen.

Social Historical Context

In the November 1943 issue of Social Process in Hawaii, Yukie Hirano, a UH student, and Yasunobu Kesaji, a 1941 graduate of UH (Ka Palapala) and likely an employee of the Territorial courts, co-authored “Notes on Juvenile Delinquency in War-Time Honolulu.”

Hirano and Kesaji tackled this subject expecting to find that Honolulu’s juvenile crime rate mirrored a wartime trend seen elsewhere. They would have been aware of the alarm being sounded across the nation: an increase in juvenile delinquency during 1942 due to fractured families and the mass migration of new workers flocking to high-paying defense jobs in various areas. They even may have been aware of specific conditions in other “war industry” centers. For example, in 1943, Portland, Oregon, a shipbuilding city, saw a rise by 14% in crime among juvenile boys, but an increase of more than 100% in crimes committed by female juveniles.

Because of the demand for war workers and the need for civilian defense volunteers, a larger number of both parents and older children were absent from home. Fathers and older brothers, whose presence might have had a steadying influence on teenagers, had been drafted, as were professionals who worked with youth – welfare workers, recreational directors, and schoolteachers. “The Child Welfare League of America estimated that of the normal 100,000 social welfare jobs in the country, 40,000 are now vacant, of which 12,000 are urgent” (p. 80).

Hirano and Kesaji had approached the topic of juvenile delinquency with the supposition that youth crime had to be up in Honolulu as well. But this was not the case. In the several months following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawai‘i citizens were living under highly restrictive martial law. Curfews and blackouts were vigorously enforced and citizens paid heavy fines for any violations. The sobering effect of Pearl Harbor and the immediate threat of invasion during the first year of the war was unquestionably a more important influence in reducing wayward behavior of juveniles in Honolulu than in similar communities on the continent (pp. 80-81).

Little wonder, the authors concluded, that in the first three months of 1942, Honolulu experienced a more than 25% decrease in juvenile crime (p. 78).

Hirano and Kesaji point out that jobs for youth were suddenly plentiful, and the increase in earning power among teens provided them with more money than most young people had ever had (p. 80). Like other RASRL writers who wrote about forces in the larger community, Hirano would have been reading local newspapers and, like B.B., had access to the Sociology Lab’s materials, which contained fellow students’ research, and perhaps had heard excerpts from morale diaries in class. They also may have sought out government reports like the US Department of Labor’s Children’s Bureau’s “A Community Program for Prevention and Control of Juvenile Delinquency in Wartime,” September 1943.

Hirano and Kesaji’s article “is based chiefly on the statistics of arrests by officers of the Honolulu Police Department and especially the Crime Prevention Bureau” (p. 77). If Kesaji was an employee of the court, the authors would have had ready access to arrest records and to the Crime Prevention Division of the Honolulu Police Department report by Capt. Madison.

According to Madison’s report, a juvenile delinquent was defined by Hawai‘i law as a minor between the ages of seven through seventeen “who violates any law of the Territory or any county or city and county ordinance or who is incorrigible, vicious, or immoral or who is growing up in idleness or crime or who habitually wanders about the streets in public places during school hours without lawful occupation or employment” (“Juvenile Delinquency in Honolulu: A Report of Trends since the Organization of the Division in 1934 with Particular Emphasis on the Two War Years 1942 and 1943,” p. 3).

It’s important to note that arrests, which are Hirano and Kesaji’s interest, are not what this map illustrates but rather cases that made their way to juvenile court. Whatever the number of cases shown on the map, the number of juveniles arrested was greater than the map’s scatter-plotting shows. As it turns out, the map illustrates but one phase in the processing of juvenile delinquents, a snapshot taken between arrest and sentencing.

Madison’s report specifies what the map doesn’t: the crimes committed and the delinquents’ gender, providing not only a larger context but a more nuanced and interesting one.

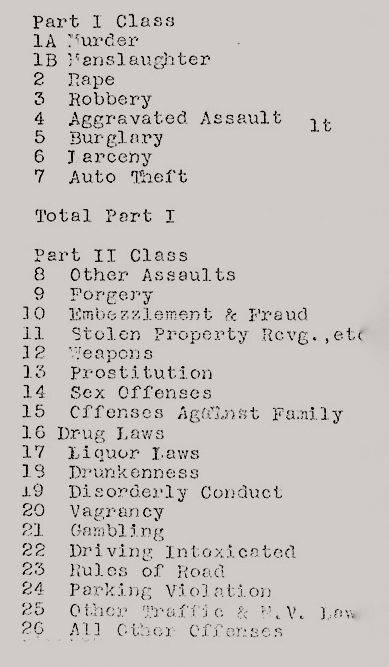

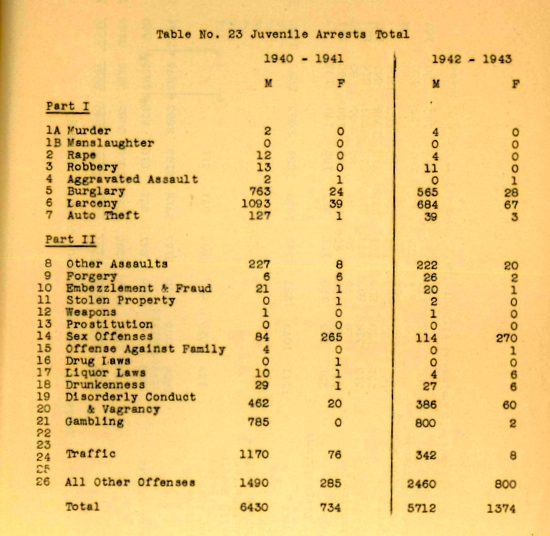

Madison notes that in Honolulu the volume of crimes coming before the Crime Prevention Division (since 1934) had gradually increased. However, in 1942 and 1943, the number of Part I crimes (see above image) decreased.

Part II crimes, however, were on the rise, making for an overall increase in crimes in 1943 as compared to 1942.

Part II crimes, however, were on the rise, making for an overall increase in crimes in 1943 as compared to 1942.

But as the statistics show and Madison points out, a very different pattern developed. Typically, the arrests of male teens outnumbered the arrest of females by seven or eight to one, but “[d]uring the war years the number of boys arrested has decreased while the number of girls’ arrests has so increased that this ratio is now only 3 to 1” (p. 6).

The impact of war resulted in sections of Honolulu being taken over for direct military purposes, and a flood of war workers only exacerbated an existing housing shortage. Madison estimated a 50% increase in civilian population since 1940. Many more women were employed and the divorce rate was up, making for “neglected children and illegitimacy” (pp. 1-2). Most important, Hawaii’s gender imbalance was estimated to be a whopping 100 men for every woman (pp. 2-3).

In 1940 and 1941 sex offenses were the largest single type of crime for girls, followed by running away from home or parental disobedience, curfew, and larceny. In 1942-1943 curfew violations by girls – being on the streets during blackout and failing to carry an identification card – led, with sex offenses closely following (p. 7). The Table above makes it easy to see not only the offenses committed but the gendered nature of crime and what society and the law meant by bad girls.

RASRL Context

Madison’s report opens with a section entitled “Cultural Background” in which he quotes UH sociologist Andrew Lind’s studies in “Culture Conflicts”:

The bases of Hawaii’s peculiar problems of juvenile delinquency are doubtless inherent in the very character of island economy and life. … The conflict between Western and Polynesian moral standards expressed itself chiefly in relationship to sex and property … descriptions of native social life are full of critical observations upon the casual sex relations of Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian youth and their casual attitudes regarding the conventions of marriage. Where European culture has made the right of the individual to require and possess property one of its cardinal virtues, the old Hawaiian culture … attached far greater significance to certain social values, such as generosity and hospitality. That western criticisms and even legal prescriptions have failed to eradicate these attitudes and dispositions among the children of Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian ancestry, even after a century of persistent effort, is revealed by the current trend of juvenile delinquency (p. 1).

Lind adds that immigrant groups in Hawai‘i – Chinese, Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, Puerto Rican, Spanish (a group not represented in our map), and Filipino – have faced the same problem in “reconciling its customs with those of the dominant American community.” Consequently, “. . . under these circumstances one can scarcely expect . . . Americanizing influences in the community to stabilize the conduct of wayward youth” (p. 1).

The only reference in the Madison report to race and culture, this quotation from Lind seems oddly out of place in a document concerned with the patterns of crime and the genders of the juveniles who committed them. Madison’s focus is on the disruptive forces to the community in the years leading up to the war and into the early war years – significantly, the deployment of servicemen to Hawai‘i and the increasing manpower needed for a war industry center. Lind places the blame on ethnicity and cultural conflict, which brings us back to our map and the RASRL Collection to which it belongs.

Race – or what we call ethnicity – was the text and subtext of every research project conducted for the Sociology Lab. Thus this map is an excellent representation of the central interest of the Sociology faculty and the RASRL writers who completed their course assignments. It also reminds us that maps, by intent and necessity, are partial. By attempting to retrace the trails that might have led to this map or the paths that simply circulated around it, we learn about the conditions that affected Hawai‘i youth during the war years. We also are able to place juvenile crime in a context larger than just “race and place.” Doing so allows us to see this portion of Honolulu’s youth as actors and not simply dots on a map.