This post offers a close analysis of four RASRL papers that focused on a slum area and transitional space in Honolulu. In addition to taking us into Pālama and its surrounding neighborhoods, these papers and maps are early examples of community and neighborhood studies, a genre that students continued to work in for decades.

The Paper: “Slum Life in Honolulu,” 1929

The Writer: Anonymous

Location in RASRL: Box A-1

To provide a sense of this writer’s focus since no map accompanies the paper, Mary Kawena Pukui et. al’s Place Names of Hawaii (1976) is offered as a guide. Although devoid of street names, Pukui’s map can provide a frame of reference.

This RASRL writer describes slums on the “outer circle of the business district.” On Pukui’s map, the surrounding areas of Chinatown are: Downtown Honolulu and Kukui (15), Kaka‘ako (16), Liliha, Pālama (7), Kalihi (6, based on Pukui’s reckoning), and Iwilei (6). The writer adds that while not all of these areas have slums, all do have poorer areas with rooming houses for the “plantation worker who quits the field for the more glamorous life of the city.”

This writer focuses on the social mobility of former plantation workers and their families who started businesses of their own and eventually bought homes in “respectable” suburbs of Honolulu (as discussed in K. A.’s paper below). As a result, by 1929 these neighborhoods had become mixed: Chinatown, for example, was no longer populated by only Chinese; Kaka‘ako was no longer “only Hawaiian”; Kalihi was more diverse than just Portuguese residents. Iwilei is dominated by Filipinos, but this writer predicts it, too, will become a “conglomeration” over time.

The defeated class is comprised of those who are financially “broke” so to speak. They have already resigned to fate and hence make no effort to better themselves. The country folks are in the majority young boys nearing the twenty year mark who find rural life too dull and too unprofitable.

This writer had good reason for asking that his name be redacted, for he – and because of his easy access to what he describes, he is likely male – may have been a long-time resident of Chinatown who did not want to put his neighbors, informants, and himself at risk.

The writer frequented Chinatown’s dingy drugstores, where some proprietors, purporting to be “doctors,” dispensed opium. He saw people on the streets bootlegging, gambling, and peddling narcotics. Japanese fishermen who resided in the River Street area downtown and whose sampans were too small to make large fishing catches were “… sometimes employed to transport opium tins that are dropped by the big liners out at sea. …” One man who came to Honolulu from Hale‘iwa couldn’t find work so he became a fisherman. Because only his first few catches were successful, the fisherman eventually agreed to transport opium for a “good profit.”

The writer says that during this Prohibition period (1920 to 1933):

Hawaiians predominate in the booze industry in Chinatown. The reason seems to be that the Hawaiians receive protection from police officers who are not prone to arrest natives. Japanese rank next in this district. They are very timid of [sic] the police officers simply because the burley [sic] Hawaiian “dicks” take great delight in arresting a Japanese.

The writer also takes note of the houses of prostitution in the area:

There are four large establishments which house from half a dozen to ten prostitutes. These cater to all comers, but especially service men. Likewise there are innumerable individuals who follow that illegal profession along River, Liliha and Kukui Streets. These are mostly Porto-Ricans and Part Hawaiians. The white establishments, aside from the four large hotels … are scattered in the more residential suburbs as Nuuanu, Waikiki, and the residential sections of Kalihi.

He comments on the area’s gangs, men in their late teens or 20s who were intermittently employed at the cannery, as stevedores, and as bartenders in “bootlegging dives”:

There is an alley in Chinatown which is the den of nine boys ranging in age from 19 to 23 years. Two of them are Hawaiians, another two are Chinese-Hawaiian and still another two Japanese, and three are Chinese – a rather unique conglomeration of races. All of them are loosely connected with their families. They frequently indulge in drinking and nocturnal visits to the “red lights” outside of their district. They have taken part in numerous escapades. …

This gang went to movies or Palāma’s Rizal and Liberty Dance Halls, places frequented by mostly Filipinos and servicemen:

Both dance halls are operated on the “park plan”: men buy tickets and pay a ticket a dance, the cost being ten cents a ticket. The girls employed there are required to dance with any man who asks them, and get half the value of the ticket. These dance halls are intimately associated with vice. Its appeal is frankly sexual. All the women employees, Part-Hawaiians, Filipinos, Whites, Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans are of loose character.

The Paper: “Community Study of Auld and Peterson Lanes in Palama,” 1930

The Writer: T.N.

Location in RASRL: Box A-7

The Writer

T.N. was born in 1909 in Honoka‘a, the child of immigrant parents. She was a member of the 1931 graduating class (Ka Palapala) with a major in education. According to the 1930-31 UH “Catalogue and Announcement of Courses,” she was living on North King Street, just a few blocks from Auld and Peterson lanes. Many RASRL writers wrote about their neighborhoods because it was what they were most familiar with. This lends the papers and maps credibility.

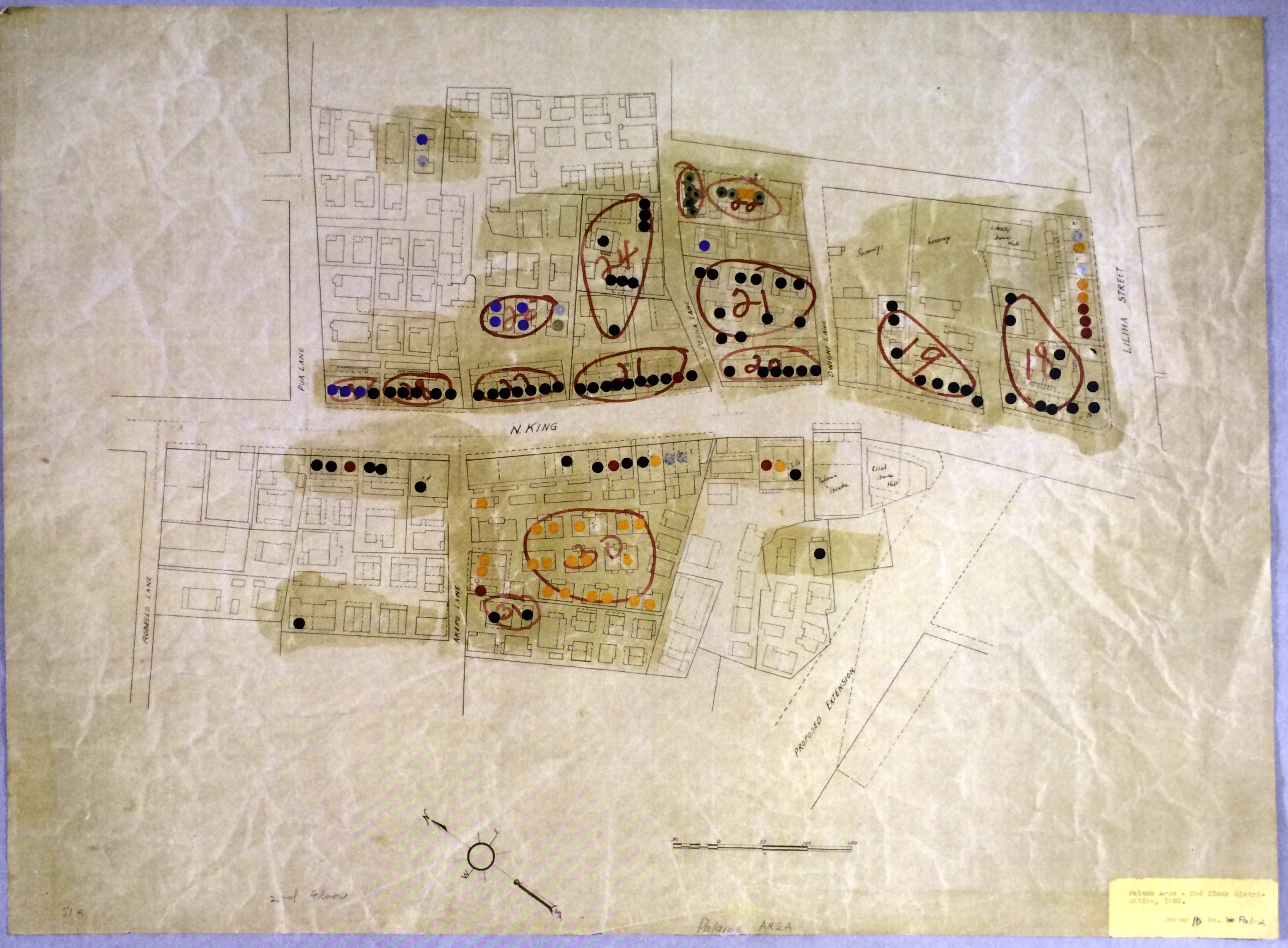

Of the papers and maps examined here, those of Auld and Peterson Lanes represent what must have taken T.N. weeks to complete. Her map is highly detailed and specific (even the trees are identifiable – papaya, avocado, palm), and as the note at the bottom right on the map indicates, this is a revised version made after her house-to-house investigation. Of the human residents, she notes their ethnicities and occupations; she locates businesses; she even points out what no longer exists, a “former banana grove on Vineyard” (top right) and includes Auld Lane’s former name, “Rice Mill Road.”

The Paper

This copy of “How to Do a Community Study” (above) is from a later period, but T.N.’s paper follows the same basic structure and includes much of the same information. The topics covered include: “… General Atmosphere of the area, the Previous and Present Day Natural Boundaries of the area, the Early History of the area, the Population, the Mobility of the People, the Economic, Social, Moral, Educational, and religious status and activities of the People of the area.” Details, from general to specific, that are not able to be included in the map, are offered in the paper: descriptions of the area’s topography, the general sanitation or lack of it, the narrow lanes filled with rubbish and garbage, the use of inexpensive kerosene for fuel rather than more costly gas or electricity.

Information about the history of an area often illustrates the movement of folks from rural plantation to urban areas and the gradual displacement of people who were previous residents. The Auld and Peterson area’s earlier Chinese residents had planted rice in the “grassland” section (see central left on map). Previously, Hawaiians had grown taro in the area.

RASRL writers were dependent on long-term residents with good memories for this kind of information. But for this community, the writer found that very few had been in the area for more than five years and some for only a few months:

To them the matter of a good or bad environment is of little concern. In fact they much prefer a bad environment where there is little social control, or social restraint or social convention because they can live as freely as they wish to – they may drink, gamble, or steal, with little interference from the police, public opinion, or their neighbors, for in such an area, little law is enforced, and hence great social and moral disorder, is an inevitable result.

She concludes by saying such residents have little incentive or opportunity to get to know neighbors and have found it prudent to mind their own business.

T.N. conducted a house-to-house survey (something that is nearly unthinkable today), and the information she gathered is as detailed as census data. Her findings are organized by race in various charts (most nearly two feet long) and include: head of household’s age, occupation, number of children, monthly income, religion, length of residence, whether the residence was owned or rented, cost of rent, where the residents lived before, reasons for changing residence, educational status, newspapers and magazines to which the residents subscribe (a gauge of literacy, education, and perhaps civic engagement), social status and membership in clubs by adult men and women in the family, political participation (voting behavior), attitude toward social welfare (contributions made), and whether they consider themselves progressive or conservative in customs, ideas, and habits.

The portion of the chart shown here is of residents who are minorities in the community: Chinese, Filipino, Portuguese, and Hawaiians. Note that the Hawaiians are not laborers but professionals (lawyer, bookkeeper) or hold patronage positions. Two were born in the neighborhood and most others are long-time residents. They vote and contribute to social welfare organizations. As noted at our related website, the absence of Hawaiian voices is lamentable; the degree to which representations by others of Hawaiians as stereotypical is often painful. The information found in this chart is a useful corrective.

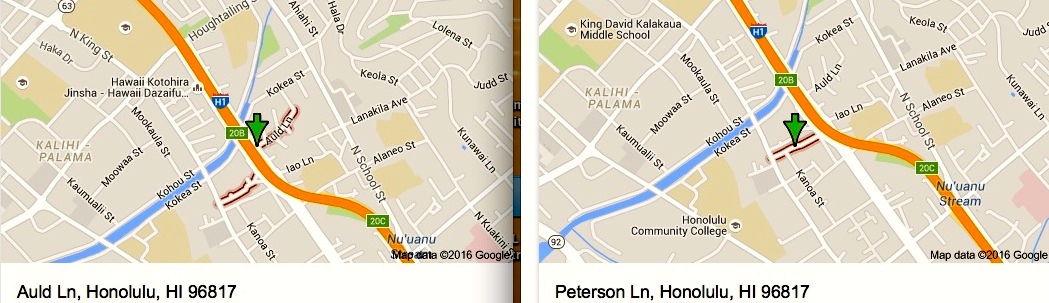

Both Auld and Peterson Lanes still exist. Although as the maps below show, they have been significantly altered by the H-1 freeway that opened in 1953.

The Paper: “Japanese Residential Movement in Honolulu,” 1929

The Writer: K.A.

Location in RASRL: Box 1 A1979, Folder 15, Urban Movement

The Paper

K.A. focused on the relatively recent arrival of Japanese families into the Kalihi-kai area around Libby pineapple plant. She did not create a map but Section 1 of the Pukui map locates the area under discussion. Today, this area is referred to as Kalihi-Pālama.

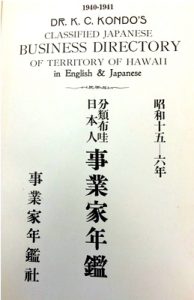

“All Japanese residents in the districts, under [this] study, in 1928 were traced back to 1911 at intervals of two years.” She gathered this information from “year books” (akin to city directories) published by Hawaii Shimpo and Nippu Jiji and borrowed from T[akuji] Onodera of the Japanese Chamber of Commerce.

“All Japanese residents in the districts, under [this] study, in 1928 were traced back to 1911 at intervals of two years.” She gathered this information from “year books” (akin to city directories) published by Hawaii Shimpo and Nippu Jiji and borrowed from T[akuji] Onodera of the Japanese Chamber of Commerce.

From only five families in 1911, the number of Japanese families grew to 213 in 1928. Most of these families were from just a few areas: sixty-six from Pālama, ten from Liliha, seven from other places in Kalihi, and four from Iwilei. The writer also gathered information on the fourteen prefectures from which the Issei had emigrated, the larger ones being Hiroshima (sixty-nine), Kumamoto (sixty-six), Yamaguchi (forty), and Okinawa (ten).

Focusing on the largest migrant group from Pālama into Kalihi-kai, K. A. noted the reasons for their move: (1) their rising economic status; (2) the area’s cheaper land prices; (3) nearby employment offered by Libby Pineapple Cannery; and (4) what the writer considers to be the most salient, the immigrants’ decision to permanently settle in Hawai‘i:

Japanese people as a whole are particularly attached to their place of birth. Practically all Japanese immigrants who came to Hawaii had no thought of settling in Hawaii permanently: they came with a hope of returning to their homes as soon as they had saved a reasonable amount of money. The sentimental attachment to their birth places ruled their life in Hawaii. They cared not how miserably they lived in what they considered but a temporary abode so long as they were able to realize their cherished hope of returning to their birth places with some riches. Consequently they preferred the tenement life to owning their homes. This attitude characterized most of the Japanese people in Hawaii until very recently and there are still a considerable number of them who are of the same frame of minds [sic] today. … The settlement and development of the Kalihikai district may be taken as a concrete proof of the changing attitude of Japanese toward their life in Hawaii.

The Writer

There is no mention of K.A. in issues of Ka Palapala prior to 1930 or in subsequent years. However, she is listed in the roster of students in UH’s “Catalogue and Announcement of Courses 1929-1930” (p. 120). For a time UH catalogs listed not only students’ majors but their hometowns as well: K.A. was a social science major from Yamaguchi, Japan. She was one of nine students from Japan enrolled at UH in the 1929-30 academic year.

Unlike K.A., Nisei writers rarely traced the origins of immigrants. As a native Japanese speaker, she may have had an easier time than local Japanese students in contacting, or even thinking to contact, and communicating with Mr. Onodera who was born in Japan according to the 1940 census.

The Paper: “A Sociological Study of Palama District Along King Street from Liliha St. to Pua Lane,” 1929

The Writer: K.K.C.L.

Paper Location in RASRL: Box A-8

Maps Location: Drawer 10, L1 and L2

The Paper

Palama is the home of a number of races. Chinese, Filipinos, Hawaiians, Japanese, Koreans, Negroes, Portuguese, Part-Hawaiians, and Porto Ricans constitute the inhabitants. The Whites neither conduct business nor live in this district.

At the time of K.L.’s survey, the buildings in this community were wooden, between ten and twenty years old and in “fairly good condition.” More commercial than residential, the neighborhood offered “no genuine community centers” unless “amusement halls can be classified as community centers,” such as the Rizal and Liberty dance halls and Palama Theater.

According to K.L., dance halls served the “lonesome bachelors of the military and naval services” and mostly Filipino and Hawaiian civilians. Patrons were charged twenty-five cents as gate receipts plus ten cents a dance with the women who earned five cents a dance. These “jitney dancers”… were of “questionable” character, and according to this writer, prostitutes sometimes worked as jitney dancers “during periods of depressed business.”

As seen in the other papers featured here, Pālama and environs were often first residences in the city for those who had left rural areas, and these neighborhoods continued to be transitional. “One party informed the investigator that he (the former) would not stay in the district longer than it was necessary.” The writer adds that as soon as residents could afford it they moved out. The Japanese, Koreans, and Filipinos chose to live among their “own kind,” while the Hawaiians were “indifferent in regard to the selection of neighbors.”

K.L. offers succinct profiles of the major ethnic groups in the area:

- The Japanese have or use public baths and their homes are in good condition. They operate businesses, such as photography studios, drugstores, rooming houses, tailor shops, furniture stores, plumbing shops, junk shops, laundries, flower shops, fruit stores, shoe stores, billiard parlors, barber shops, restaurants, cafés, dry goods stores, and auto stands. These folks live mostly above businesses. Other Japanese in the area are carpenters or fishermen. “In one of the [Japanese] camps they conduct a variety of occupations including the making of their well-known national beverage [sake] which they use … to good advantage.”

- The Chinese “are a bit clever in the business trade. When they run a grocery store, they also include a butchery, this is done with the view of keeping patrons within the confines of their establishments.” Some other Chinese own drugstores where they sell “native herbs”; others operate laundries, restaurants, chop sui houses, and a “bean factory.” “It is a common truth that the Chinese do not like the barber trade, hence Chinese barbers are conspicuous in their absence not only in the district but elsewhere in the city also.” Most of this group, he added, is from Canton.

- The Koreans run small concerns: cafés, shoe shops, tailor shops, furniture stores, laundries. “It is to be noted that this district has the most business establishments operated by Koreans as compared to the other sections of the city. This is due to the fact that Palama is the home of the largest number of Koreans in Honolulu.”

- Most of the Filipinos are bachelors, the writer says, but some have Hawaiian wives. Very few Filipinos own businesses except for one café, two billiard parlors, and a tattooing shop outside the Rizal Dancing Hall.

Here in Palama one finds remnants of the ill-fated strikers who attempted to stir the sugar barons to action some years back. It is believed that a large number of these people work only during summer pineapple season, and it can readily be seen that a considerable portion of the industrious school children are deprived of the opportunity of their vacation earnings.

- Hawaiians and Puerto Ricans do not operate businesses but are laborers with the Rapid Transit Co., the Railway Co., the City Waterworks, Iron Works, and some are stevedores or road workers. The writer says that “street brawls, knife frays, and murders arising out of gambling and jealousies over certain women are not infrequent sights.” He says that these groups are at a economic disadvantage when they must compete against the “more energetic Orientals.”

- Portuguese and “Negroes” are dismissed as not offering “any real sociological significance.”

Palama really represents the lower strain of Honolulu’s social life. A deserted town in the day, but the night presents a lively scene; people from all corners make the place go merry. Yet in the midst of these night furies, Palama is a poor man’s town.

The Maps

Using commercially prepared maps, K.L. applied scatter plotting to indicate businesses and residences in this section of Palāma along North King Street. In addition to seeing the changing topography and development of Honolulu – notice the proposed extension of Liliha street at the bottom right – we learn about the ethnicity of the residents, the area’s shops and businesses on the first-floor map (above image), and the ethnicities of those who reside on the second floor (image below). There are no three-story structures in the area.

What is missing on the maps is explained in K.L.’s paper, the codes for the colored dots:

- Black dots, which are greatest in number, represent Japanese residents in “Japanese Camps,” Sections 1, 3, 6, and 11. However, the Japanese are scattered throughout nearly all sections and along King Street.

- Gold with black dots represent Puerto Ricans who reside in Sections 13 and 14.

- Yellow dots represent Filipinos who are mostly in Sections 2, 4, 14, and near King Street.

- Chinese (red), Hawaiians (blue), Portuguese and “others” (gold) reside in Sections 4, 5, 7, and 10 .

- Silver with a red dot signifies Koreans who are primarily in Sections 7 and 8.

The Writer

K.L. concludes his description by pointing out the scarcity of Chinese in the area. This writer is Chinese and his family may be one of the few residents left in an area that at one time was nearly exclusively Chinese. He may also have been one of the “industrious school children” who was “deprived of the opportunity of their vacation earnings” by the Filipino residents who took the summer jobs in the pineapple cannery. By 1932 K.L. was a junior at UH and according to Ka Palapala was too “camera shy” to show up for his class picture. He subsequently attended Drexel Medical College and was living in New York City at the time of the 1940 census.

RASRL Context

The UH campus population in the late 1920s and 1930s (Ka Palapala) was as transitional as the neighborhoods under study here with Haole barely edging out Japanese (21) as the largest number (23) among the 59 candidates for BAs in 1931. Hawaiians, although not in great numbers at UH, were among campus leaders. The transition was in part due to simple demographics: “In 1900, the nisei comprised a mere 8 percent of the Japanese population. By 1910 they were 25 percent. In 1920 … the figure had jumped to 44.5%” (Franklin Odo, No Sword to Bury, p. 37). Of the 252 students in UH’s 1941 graduating class, 51 percent were Japanese (Ka Palapala).

Social Historical Context

Chinatown, in particular, has a history of being an area where both commerce and vice flourished:

In 1900, more than half of the more than seven thousand souls in Honolulu’s “Chinatown” were Japanese. Hilo, on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, was rapidly becoming a Japanese enclave. … There were Japanese wholesalers and retailers, newspapers, theaters, hotels. … Several identifiable Japanese gangs in Honolulu oversaw highly profitable gambling and prostitution activities; one even printed and circulated its own newsletter (Odo, p. 22).

At the time Anonymous did his survey, Chinatown was populated by unmarried laborers and up through World War II, a frequent stop for servicemen looking for sex and other diversions. This area had a thriving prostitution trade well before the huge influx of defense workers and service personnel in the 1930s.

Early in K. L.’s paper, he says this:

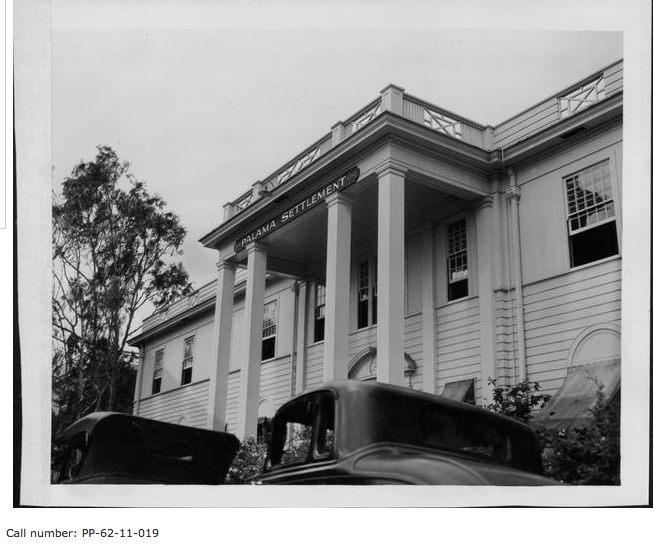

The Palama Settlement, though not in the premises in which this theme deals with, draws a large number of this area’s people to its frequent dance parties. It is claimed that it has practically been made a Filipino dance hall owning to the large Filipino congregation present at its dancing functions.

“Reflections of Palama Settlement,” a collection of more than thirty oral histories compiled by the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Center for Oral History, provides a brief history of Settlement from its beginnings in 1896 as the Pālama Chapel on King and Liliha streets to its evolution as a settlement house in 1905. In 1925, shortly before these community studies were completed, Pālama Settlement had moved to its present location on Vineyard Boulevard and Pālama Street.

Pālama, like other settlement houses, offered recreational facilities, athletic competitions, social and community service clubs, classes in music, arts, and various vocations. Some classes were designed to help immigrants assimilate to American culture. Over many decades, RASRL writers commented on the services the Settlement provided them and their families; some writers worked part-time at Pālama Settlement advising youth groups. One served as a piano instructor: “Never did I realize that a hobby [playing piano] would get me a job paying approximately half of my way through college” (S. I., “Human Relations in a Job Situation,” 5/19/47, RASRL Student Papers Box A-6).

Pālama Settlement offered dental and medical services for the poor and working classes and an outpatient clinic that provided a screening and treatment center for venereal disease, the only VD clinic in Honolulu during the 1920s and 1930s.

These community studies provide vivid snapshots of central Honolulu and its population in 1929 and 1930. They call our attention to the mobility of Hawaii’s people, from plantation to the urban setting; illustrate the shifting ethnic composition of Honolulu neighborhoods; and presage the challenges Hawai‘i would face in the years leading up to the War.

Special thanks to Reimi Davidson for her research on Pālama and Pālama Settlement.