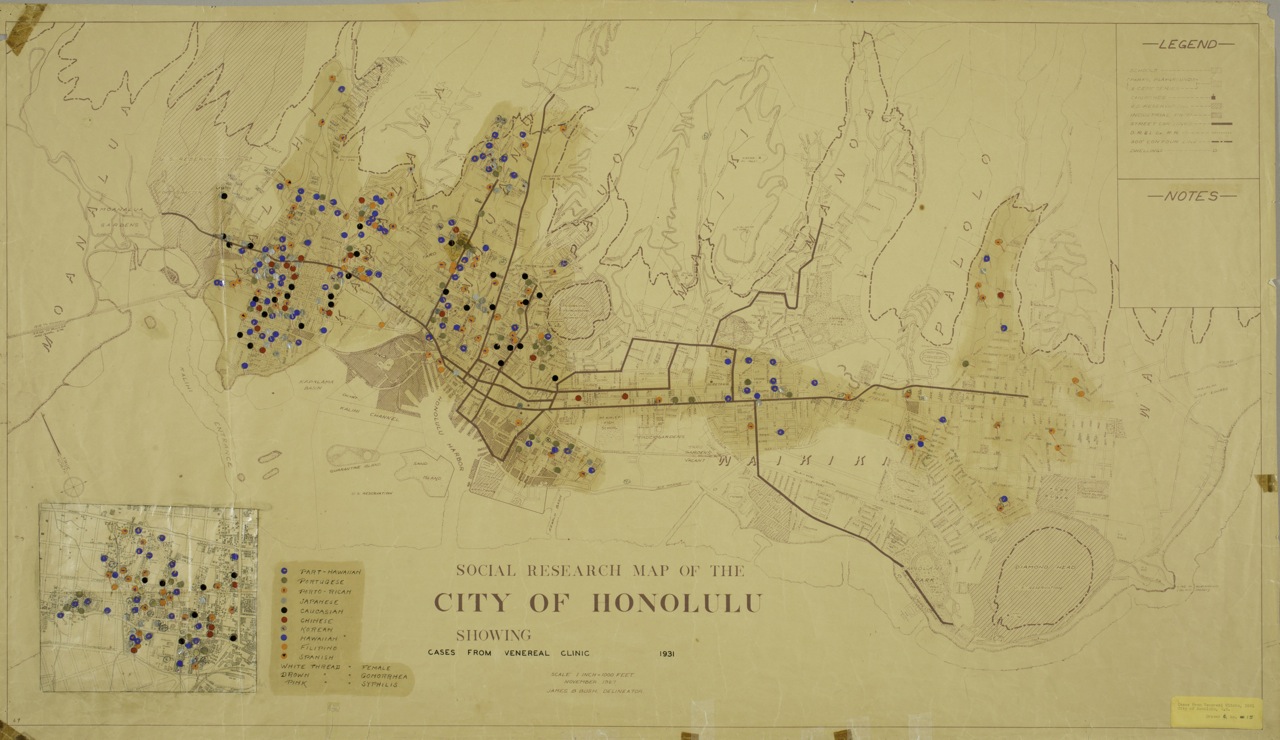

Map location: Drawer 6, No. 15

The subject of this map is the distribution of cases of venereal diseases in Honolulu. It shows the residence of patients treated at the Pālama Settlement Venereal Disease clinic. In addition to dots that indicated the ethnic background of the patients, the mapmaker added white threads when the patients were female. The map also uses colored threads to specify the sexually transmitted infection treated, brown for gonorrhea and pink for syphilis.

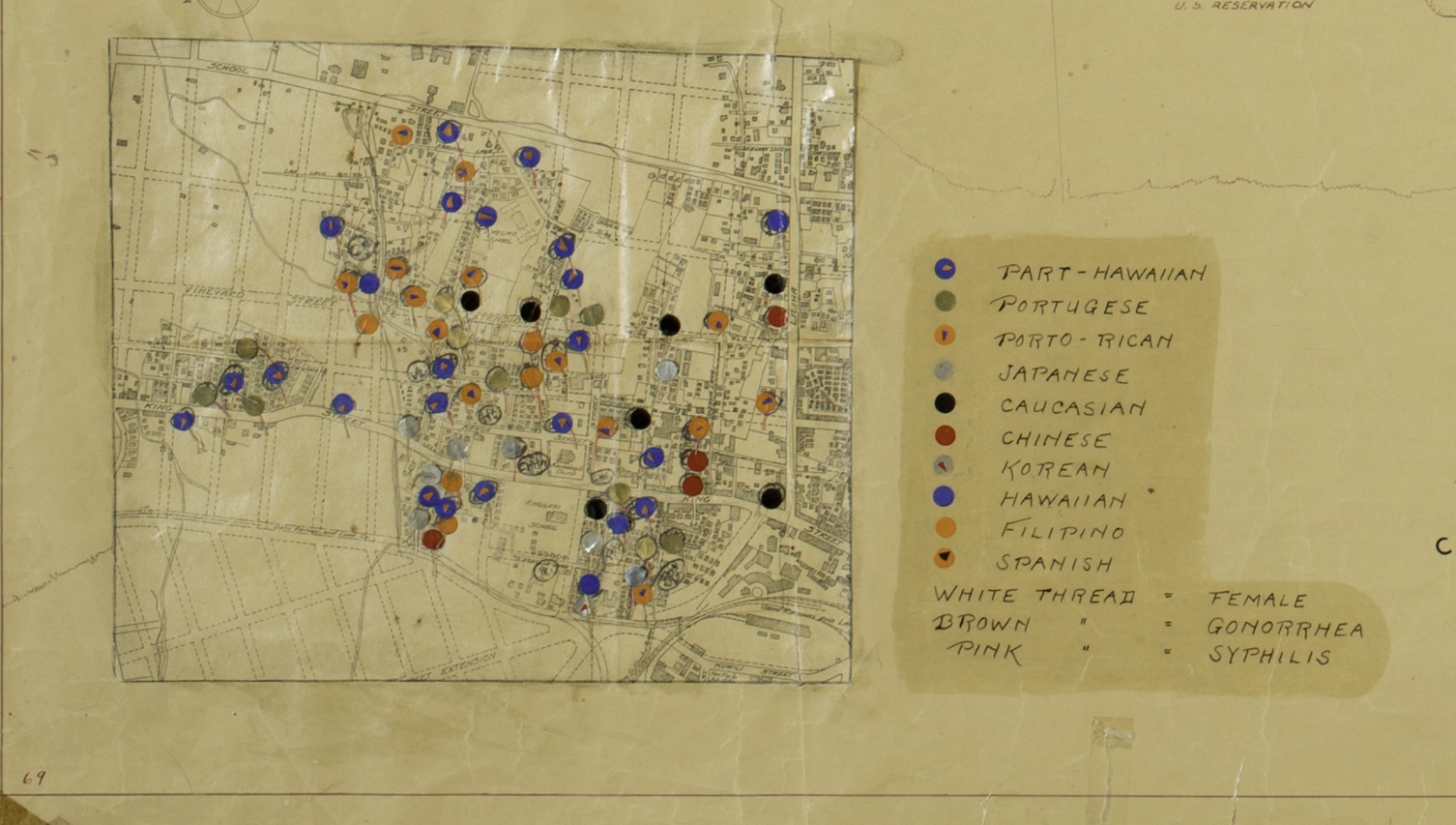

This large map contains an insert that highlights the neighborhoods of Kalihi-Pālama, Iwilei, ‘A‘ala, and downtown Honolulu, where venereal disease cases were most concentrated. Pālama Settlement, the only clinic that treated venereal disease, is located in this area.

The dots likely indicate the residences of those treated at the Clinic. Most of the cases shown here and treated at Pālama’s Venereal Disease Clinic lived in the area bounded by School Street (mauka) and the Iwilei section (makai direction), Liliha Street (Diamond Head direction), and Middle Street (‘ewa direction). One case was near Ft. Shafter (‘ewa direction) and a few were scattered along King Street in Mō‘ili‘ili and Kaimukī

The map insert below highlights the neighborhoods of Kalihi-Pālama, Iwilei, ‘A‘ala, and downtown Honolulu, where venereal disease cases were most concentrated. Pālama Settlement is located in the vacant area on the inset, left of center.

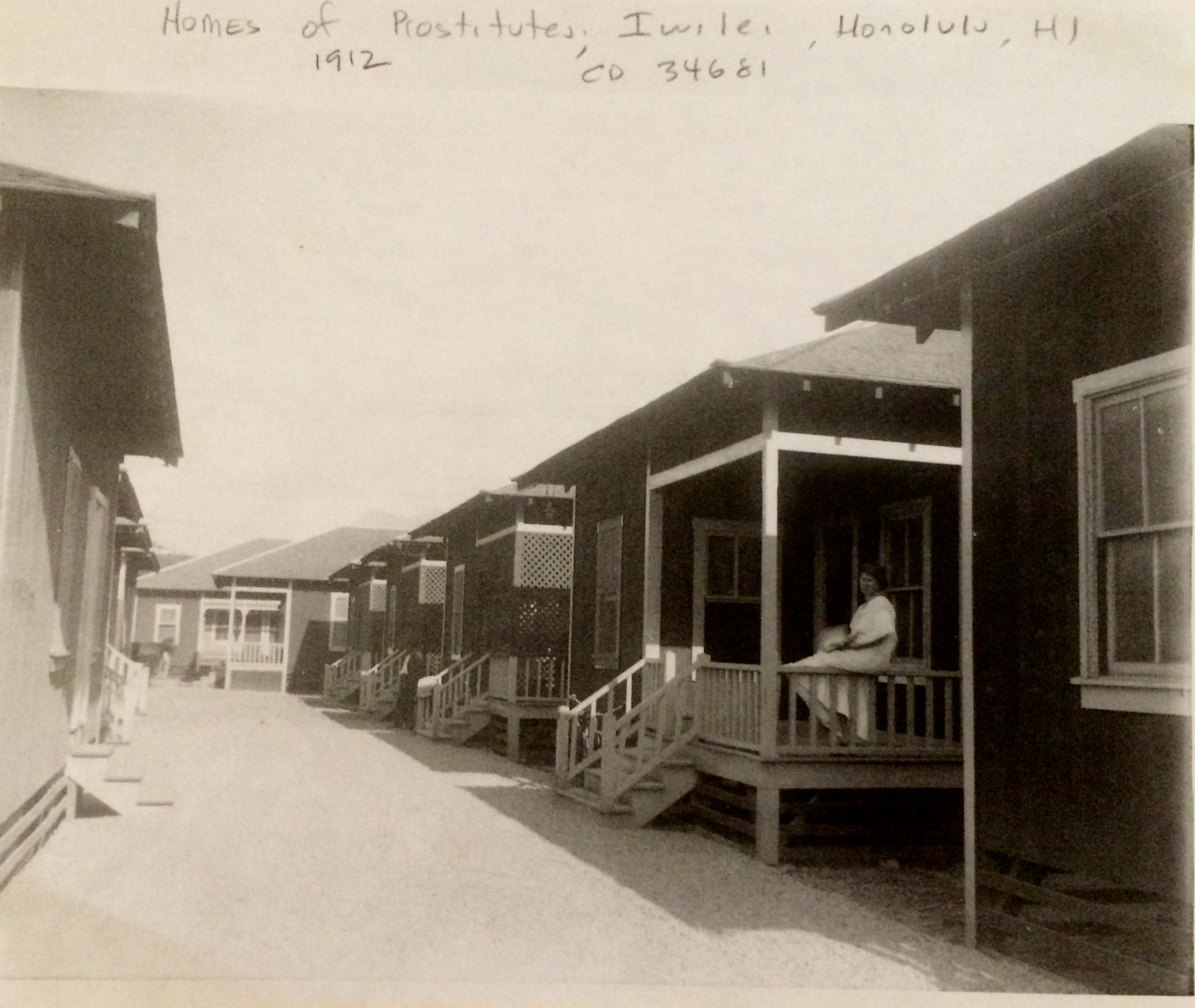

We are left to wonder why the mapmaker chose to highlight the number of women who received treatment from the Venereal Disease Clinic, especially when gender was rarely noted on other maps. But what we do know is that any discussion of venereal disease from the early 1900s onward invariably includes an examination of the problem of prostitution.

Richard Greer’s “Collarbone and the Social Evil” briefly describes the tangled history of prostitution in Iwilei (whose English translation is “collarbone”) from the 1800s to the early 1900s. His focus is on the competing attitudes toward and approaches to the trade: legal, extra-legal, outlawed, scorned but isolated and regulated. The “Report of Committee on the Social Evil,” Honolulu Social Survey, May 1914, one of whose committee members was Pālama Settlement’s Director James Rath, also provides a thorough examination of the problem of prostitution in Honolulu. By 1931, some things had changed, but the most salient factor for the persistence of the “social evil” remained: the preponderance of single men, including large numbers of soldiers and sailors.

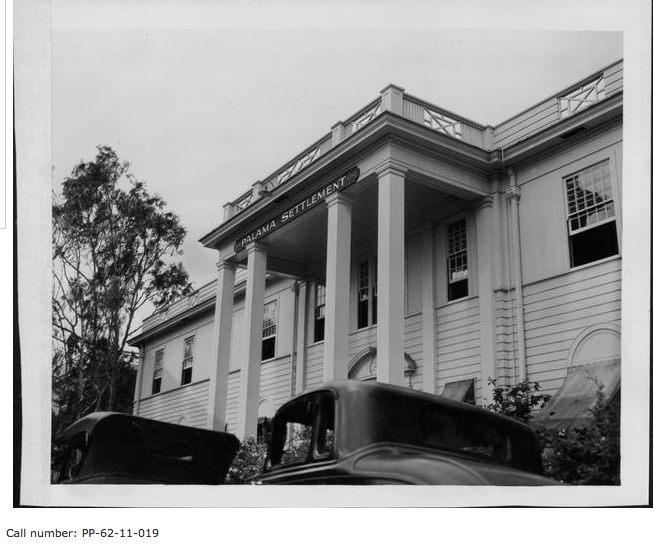

At the time this map was created, Pālama Settlement was providing a variety of services to residents of the surrounding area. Although no specific paper is linked to the map, the RASRL Collection contains community studies of the Pālama neighborhood – a large area that encompassed Kalihi, Iwilei, ‘A‘ala, and downtown Honolulu. The population in this part of Honolulu was a mix of indigent residents as well as laborers who had left plantation work for jobs in the city and to start businesses of their own.

Pālama Chapel, forerunner of the Settlement, was founded in 1896 by banker and philanthropist P.C. Jones and directed and supervised by Hiram Bingham, Jr. and Revs. J.P. Erdman, A.C. Logan, and Henry P. Judd. It had a distinct “missionary spirit” (Warren Nishimoto, “The Progressive Era and Hawai‘i: The Early History of Palāma Settlement, 1896-1929,” p. 174).

With the outbreak of the bubonic plague in January 1900, authorities attempted to control the plague through burning infested areas of Chinatown. The fire got out of control and left thousands homeless. In response to the destruction of Chinatown, tenement structures were erected across Nu‘uanu Stream in Pālama. The Chapel attempted to provide health care for these residents, but was overwhelmed by the enormity of the task. Consequently, Jones sought the advice of Dr. Doremus Scudder of the Hawaiian Board of Missions. In 1905 Scudder recruited James Rath and wife Ragna from Massachusetts, to assume leadership of the Chapel. The Raths made it clear they were social workers and not missionaries and in keeping with the practice of other settlement workers, moved into the Pālama neighborhood, on Desha Lane in Iwilei.

In 1906, the Chapel was renamed Pālama Settlement. Following the philosophy and practices established at Jane Addams’s Hull House in Chicago, the Settlement offered those who lived in the neighborhood a variety of educational, recreational, and medical programs. As with other settlements, Pālama’s mission was to assist immigrants in assimilating to American culture through evening classes in English, American history, civics, and geography; instruction in domestic science; and a variety of enrichment classes (Pālama Settlement untitled brochure, no author, no date, PS Archive, Box 46, various folders).

In 1925, the “new” Settlement opened on eight acres with nine buildings on the corner of Vineyard Boulevard and Pālama Street. In 1929, Pālama Settlement assumed control of the venereal disease clinic from the Board of Health.

Considerable care must be given to insure that patients, so far as possible, by means of personal talks with the physicians, are brought to understand the seriousness of these [venereal] diseases, and the importance of proper intensive treatment over a long period of time. Provision should also be made for follow-up of cases and for the study of family problems and the prevention of recurrent cases. … Cases which refuse or neglect to continue treatment to a successful conclusion should be followed up by letter, by personal visit, and if necessary, by police visit (Philip S. Platt, Director, Pālama Settlement, editorial Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1/9/29, Pālama Settlement [PS] Archive, Box 77 Folder 10).

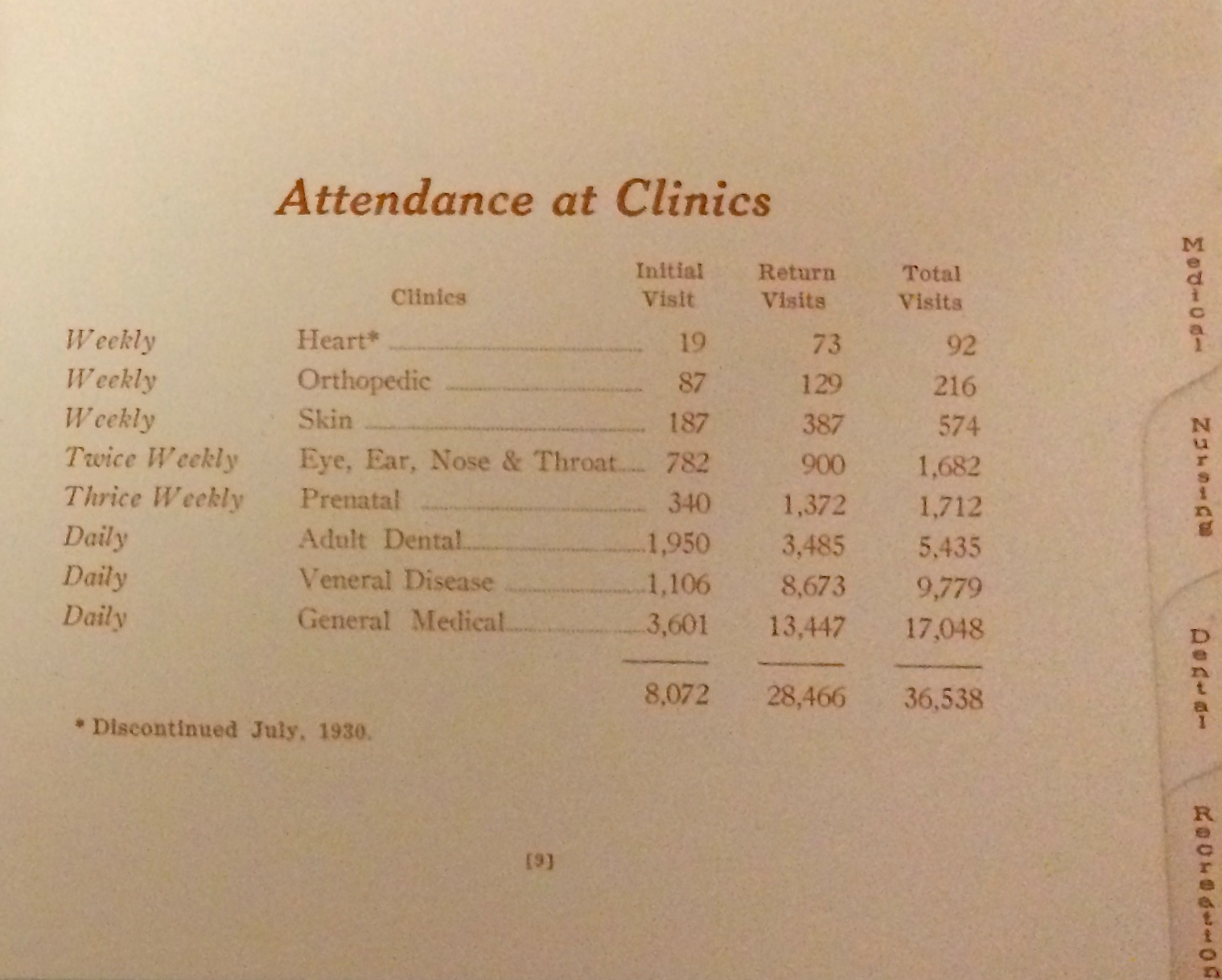

Pālama Settlement’s 1931 Annual Report below aggregates the number of those treated for venereal disease by initial and return visits. The number of patients who returned to the Clinic for subsequent treatments until they were free of the disease would have been a measure of the Venereal Disease Clinic’s success in tackling this public health issue.

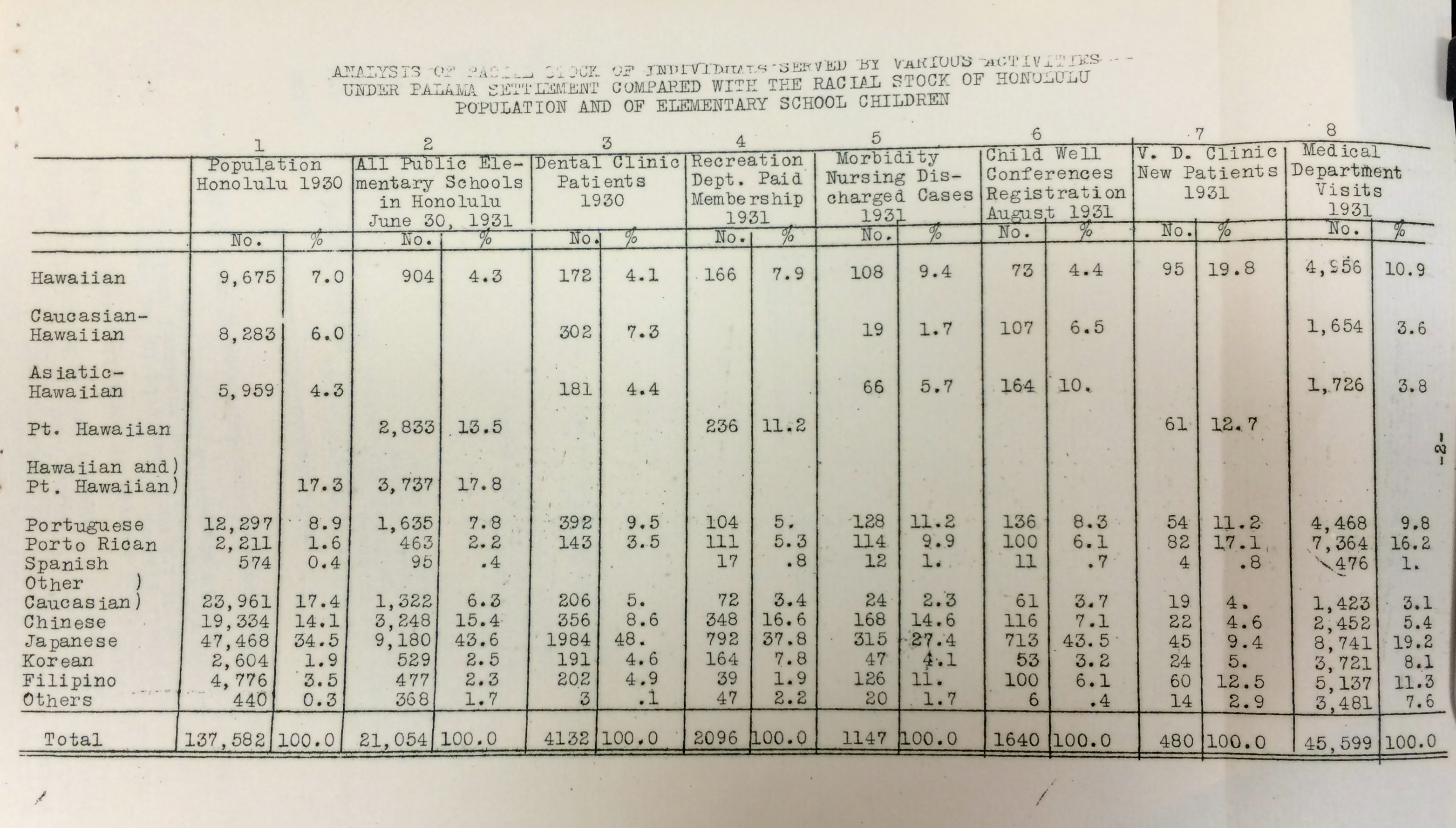

The following image, also from the 1931 annual report, provides a breakdown by ethnicity of those using the Settlement’s medical services. The number of new patients to the V.D. Clinic is located in the second column from the right:

According to the chart, whose numbers roughly correlate with the map’s, the groups with the highest number of new cases treated are Hawaiians (blue), Puerto Ricans (orange with black), and Filipinos (orange). The report doesn’t provide statistics by gender, but the silver dots – Japanese – have somewhat more white threads than other groups.

In a 1938 report, Dr. Richard K.C. Lee provides an overview of the Clinic:

Palama Settlement is a public health and social welfare center located in the city of Honolulu, supported by endowment funds, private donations, and institutional receipts from the Chamber of Commerce and City and County of Honolulu. It operates a venereal disease clinic which is the only one in the city of Honolulu and the largest in the Territory [and is] within walking distance for the many thousands of people of all nationalities living in that area who belong to the lower income group. For those not within walking distance, there are bus and street car lines connecting with all the districts of Honolulu (“A Study of the Venereal Problem in the Territory of Hawaii,” 1938, pp. 45-46).

In order to accommodate working people, the Clinic had evening hours with a fee of 25¢ per clinic visit “since the majority of these patients belong to the working class” (Lee, p. 47).

The Clinic’s records contained the sources of the disease and their contacts, notes on medical examinations, and a patient’s past and present history, discharge, and treatment data. Lee explains the Clinic’s referral and intake system:

The cases attending the venereal disease clinics are generally referred through the Palama general dispensary where the patients are given their physical examinations, Wassermanns and Kahn tests. Cases are also referred from other sources, as private physicians, hospitals, maternal health conferences, CCC camps of Oahu, and penal institutions (Lee, p. 47).

In a 1930 radio speech, Pālama Settlement Director Philip S. Pratt opened his talk by quoting from “The Great Imitator,” a document published by “one of the large life insurance companies” that several years previously had run full-page ads in US weekly and monthly magazines.

Mankind’s most dangerous enemy is syphilis, otherwise known as lues or blood disease. It takes the form of many diseases, masking as rheumatism, arthritis, physical exhaustion or nervous breakdown. It may seem to be a form of skin, eye, heart, lung, throat, or kidney trouble. … Most tragic of all, it often attacks the brain and spinal cord. It may result in blindness, deafness, locomotor ataxia, paralysis and insanity – a life-long tragedy. No wonder it is called ‘The Great Imitator.’ . . . It is estimated that about thirteen million persons – one out of ten – in the United States and Canada have or at some time have had syphilis.

If a way to urge people to seek medical attention from the Clinic was to scare them to death, this campaign must have been effective:

It will interest you to know that we are receiving from 20 to 40 new cases of these diseases [at the Clinic] each month, that over 200 cases are at the present time under treatment, and that each month we are giving some 900 treatments. The hours of the clinic have been from 12:30 to 2:30 Mondays and Thursdays. Outside of the regular clinic hours, patients come for routine treatment in the hands of the nurse and the male orderly. The work has become so heavy that we have been obliged to make provision for two evening clinics, and tonight at this very hour our first evening clinic is being held. That value of the evening clinic is that men who are employed cannot attend the clinics during working hours without danger of being discharged and this keeps many men away. The evening clinics will be conducted from 6:00 to 7:30 every Monday and Thursday nights. … Remember, if such persons are unable to pay a private physician, Palama’s clinic will accept them in strict confidence and treat them free or for a purely nominal charge.

Platt also challenged Territorial authorities to do at least as well as the military had in getting venereal disease among the troops under control:

The battle against these diseases is barely begun but why should not Honolulu’s civilian population receive the same enviable record which Hawaii’s military force has achieved, namely the lowest venereal disease rate of any of the army corps. This lies within our possibility if we frankly and fearlessly face the challenge before us (KGMB radio broadcast script, PS, 8/25/30 77-10 Departmental Records/Medical Depart 1906-1947/ Venereal Disease Clinic).

RASRL Context

We have found no paper to accompany this map. It may have been created for an assignment for the Sociology Department’s course on “disorganization” or by Sociology Lab staff for public lectures the sociology faculty routinely offered. We do know that in 1930 Andrew Lind published two articles, one concerned primarily with the breakdown of family control as measured by rates of juvenile delinquency (“The Ghetto and the Slum,” Social Forces, Dec. 1930) with a focus on the neighborhoods featured on our map. The second article could have well served as a lead-in to a study of venereal disease and the production of this 1931 map:

… with regard to prostitution. The area of heavy concentration of vice extends a considerable distance into the middle-class oriental section along the Nuuanu gradient. The haole proprietors of these houses may violate with impunity the taboos of the oriental residents since their disapprobation of figures so slightly with the police or with the haole patrons. The high concentration of prostitution in the Palama and Central slum areas represent the lower forms such as street-walking and brothels (Andrew Lind, “Patterns of Social Disorganization,” American Journal of Sociology, Sep. 1930, p. 216).

This remarkable map, when placed in the context of community studies about this area of Honolulu, showcases the vital work done by Pālama Settlement in its battle against a serious public health issue. It reminds us of the on-going movement of Hawai‘i residents from rural areas into the city and the pressures these communities experienced as a result of a surfeit of single men, civilian and military, a demographic that would only increase during the 1930s and the war years. We also have a renewed appreciation for the work of RASRL writers whose efforts constituted the substance of faculty research. But what might be most notable about this map is its highlighting of gender, offered in the one way that the sociologists’ could make room for such a discussion: in the context of women’s work. In this case, sex work.