The Paper: “Changes in a Rural Community – Haleiwa,” 1939

The Writer: N.S.

Location in RASRL: Box A-5

and

The Paper: “A Community study of Haleiwa, Waialua, Oahu with Some Comparison to that of Madison, Wisconsin,” 1940

The Writer: E.L.

Location in RASRL: Box A-3

N.S.’s and E.L.’s papers and maps provide contrasting yet complementary views of Hale‘iwa and changes its inhabitants experienced from the late 1920s until 1940. These documents illustrate how ethnicity and class shaped RASRL writers’ understanding and portrayal of their communities.

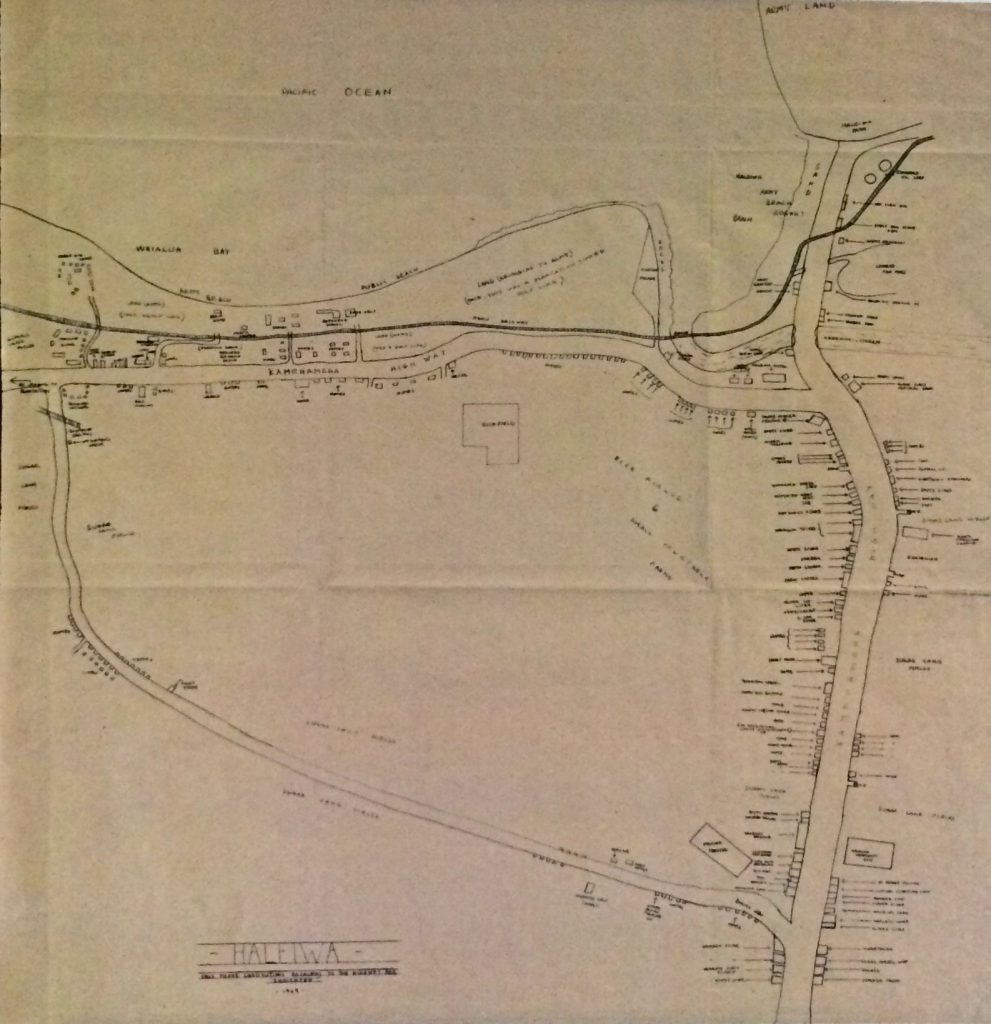

This map of Hale‘iwa is what N.S. saw in 1939. The map’s orientation locates the ocean and beaches at the top with Kamehameha Highway running parallel and then curving mauka towards O‘ahu’s North Shore. Pa‘ala‘a Road, at the bottom of the map, connects with Kamehameha on either end, enclosing mostly sugar cane fields with scattered rice and vegetable fields. Most of the businesses and homes are along Kamehameha Highway, particularly the portion that leads to and from O‘ahu’s North Shore.

The map reflects major themes in the writer’s paper and her relationship with the residents who remember her. The most important aspects of her map are the business concerns that still existed in 1939 and who owns them, and coastal areas “belonging to the Army”: a section of what had been a public beach, an area that had been a golf course operated by Waialua Plantation but had gone to ruin, and Hale‘iwa Park land.

The Writer, N.S.

Like many of her peers, N.S. found it difficult to distance herself from the subject. Unable to maintain scholarly objectivity, she apologizes before proceeding with her analysis. Her paper opens with this:

Haleiwa was my home town. I spent my early childhood there, and all the memories that I have of Haleiwa are pleasant ones. It is now fully eleven years since I have left Haleiwa to live in Honolulu.

She doesn’t explain why her family left in the late 1920s, but she does say that young people with any initiative and ambition leave for Honolulu or elsewhere “to seek greater opportunities in all fields both economic and social.” She adds

Even when they come back [to Hale‘iwa] there is no place for them. They have become much too urbanized and sophisticated to fit back into the life of the community. They cannot make a satisfactory living[,] for their business is usually located or done in the city. Their interests are such that they find no outlet for them in Haleiwa.

N.S. could have been describing herself. A member of the class of 1940 with a major in social science, she was an active member of the campus community. She was senior class secretary; sat on the councils of the Theatre Guild and the Associated Women Students (AWS), whose objective was “to promote the welfare of all women students by cooperating with the women’s organizations, evaluating the activities and needs of women students, and by assuming the responsibility for activities that cannot be assumed by other groups.” She was a member of Wakaba Kai, the campus sorority for women of Japanese ancestry, the YWCA, the Oriental Literature Society, and the University Japanese Club (Ka Palapala, 1940). She certainly had ambition and showed initiative, not uncommon traits of RASRL writers.

N.S.’s Paper

I did not realize how great was my sentiment for Haleiwa until I began to write this term paper. To begin with, I had planned to write up this paper from a purely objective point of view, but the deeper I went into the subject and the more trips I took, my paper gradually turned into a subjective treatment of Haleiwa. I could not write it in any other way so I left it as such.

Her method was to interview and survey residents. She sent out questionnaires, and of the forty-seven she sent out, only eight were completed in full. She hoped to talk to the “old Japanese country doctor” who had been one of the first to settle in Hale‘iwa, but he had returned to Japan.

In 1939, the writer finds Hale‘iwa both depressed and depressing. Even the climate is disappointing: dry, hot, and the air so salty it “rusts things,” making it nearly impossible for people to keep their homes clean. Even trees and plants look dusty and faded. N. S. feels that outsiders seeing Hale‘iwa must think it is “a terribly shabby place.”

Eleven years back, when I lived in Haleiwa, it was a beautiful and peaceful place. To begin with there were more Hawaiians living there. They left things pretty much as they found it, and oft times I think this is the best policy.

In a recollection suffused with nostalgia, she describes a particular Hawaiian family and its centrality to the community:

The Hawaiians made the community a place of happiness. … At the head of the family stood the aged mother and father. With them lived their sons and daughters and their children. Aunts and uncles lived with them too. In all there were 31 of them, all living under one roof! Besides this there were visitors staying constantly with them on weekends and other holidays. Their house was a huge structure which rambled on and on from the main center building. As the family increased a new wing was added to the already long structure. I distinctly remember that every year in March this family would have a homecoming luau for their friends and relatives and especially for the in-laws. At this luau practically the whole neighborhood would turn out to help them.

Some of us youngsters would be sent out to the beach to gather seaweed, shrimps, and shell fish. The older boys would be asked to pound the poi; taro being grown in their own backyard. The older girls would make the sweetened delicacies such as cocoanut pudding. Other experienced men and women would help in the steaming of mullet and the seasoning of the squid and shell fish. The aged parents always supervised in the roasting of the pig. … Everyone was free to come and partake of the food and entertainment. It was a grand affair and lasted for two or three days. … There was something about this family that commanded respect and everybody loved them.

N.S.’s description is a picturesque but sentimentalized portrait of the Hale‘iwa of her childhood. She remembers a Japanese fishing village with sampans dotting the mouth of the Anahulu Stream. The town had once boasted an eighteen-link golf course open to all and some of the Japanese kids served as caddies. On weekends, folks came from Honolulu to stay at the Haleiwa Hotel.

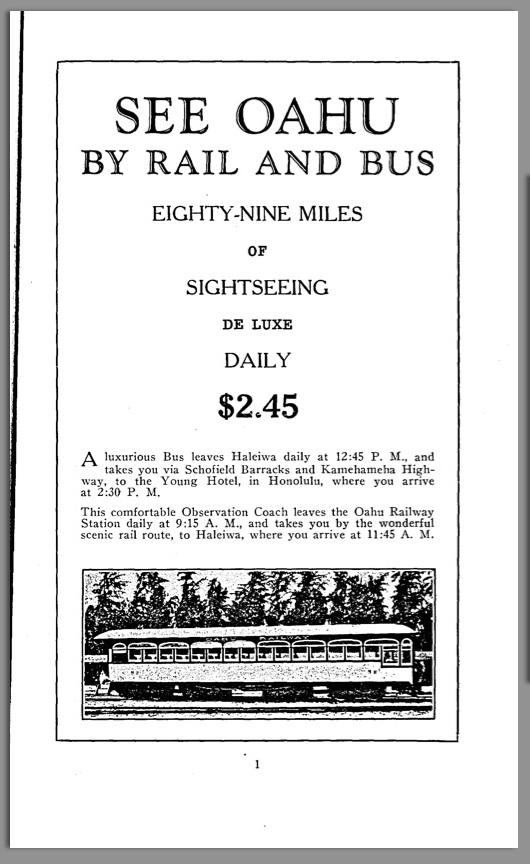

The railroad station hummed with activity as it loaded and unloaded passengers. . . . We gathered at the railroad station twice daily to look at all the passengers who got off the train. When I think of it now, we must have really looked like country children standing there and gaping at all the visitors.

Hale‘iwa was the site of Fresh Air Camp, operated by Pālama Settlement in summers to provide recreation for children who lived in Honolulu’s tenements. But during the rest of the year, Hale‘iwa residents used the area as their picnic grounds. Each April 14 Japanese residents celebrated the Japanese Emperor’s birthday by sponsoring a day of races or “undo-kai.” The day ended with the celebrants singing “Auld Lang Syne” in Japanese.

Hale‘iwa existed because of Waialua Plantation. Its small businesses provided workers with goods not available at the plantation store and served as a place for both plantation and Hale‘iwa residents to socialize. Eventually, the Plantation store began offering goods their workers wanted, and Waialua Plantation began improving the schools in order “to keep the young people from emigrating.” Andrew E. Cox Junior High School was founded in 1927, and in 1937 was enlarged to include higher grades and renamed Waialua High School. At the time of N.S.’s report, children of Hale‘iwa as well as Kawailoa and other “outlying camps” attended the high school. In all, she says, there were twenty-nine teachers with over 800 children. (The Teachers’ Cottages are on the corner of Kamehameha and Pa‘ala‘a, at the top left on the map.)

“Off Duty Servicemen relaxing on the beach, Haleiwa 1944” — Provided by the U.S. Army, U.S. Army Museum of Hawaii, Ft. DeRussy

For the writer, the changes enacted by Waialua Plantation are a mixed blessing – driving out Hale‘iwa businesses but providing solid educational opportunities to local children. But the presence of the US Army is something about which she feels great bitterness. The once “beautiful Waialua Bay now belongs to the Army,” taking over two portions of the beach and banning civilians” who now must travel to the Windward side or Honolulu for beach swimming.

There does seem to be a definite racial discrimination at this point, for I’ve noticed that [when] the white people swim there . . . they are asked whether or not they belong to the Army, but when Orientals, Hawaiians, or Fillipinos [sic] come to the beach they are told to leave at once. Even among [the Army’s] own ranks there is a marked class distinction. The Waialua Bay beach is for Officers alone, and the Haleiwa beach is for the soldiers.

In an interview with one resident, the writer asks if the woman speaks to her neighbors. Her answer is why bother “for they would soon be leaving for they were Army officers.”

The families which I visited welcomed me most cordially for they had known me when I was but a child. They seem to have gotten more out of me than I did of them, but one thing that I did find out was that their social life was not very satisfactory. Their friends lived at a considerable distants [sic] from their house. Their immediate neighbors were Army officers whom they hated.

E.L.’s Maps

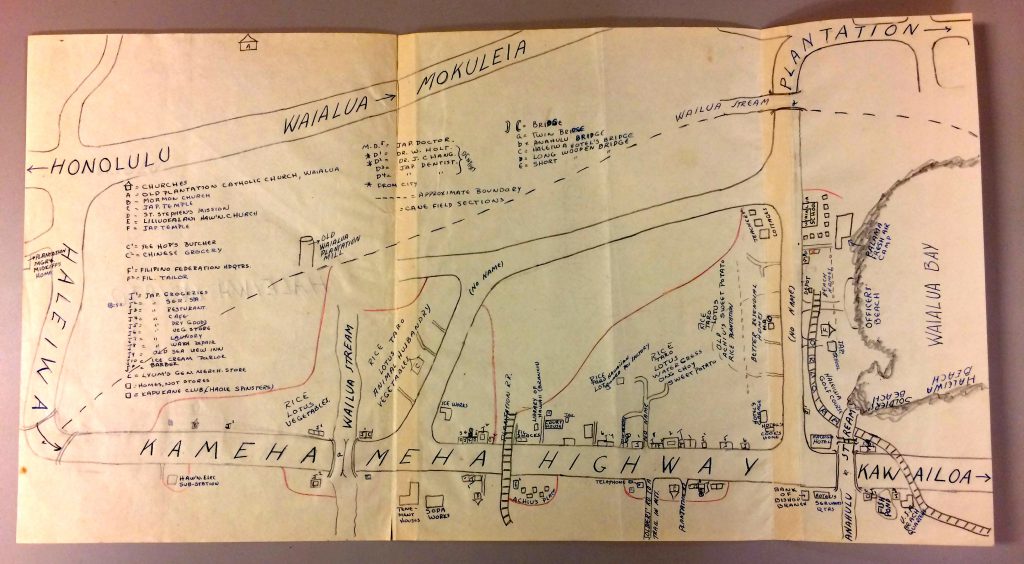

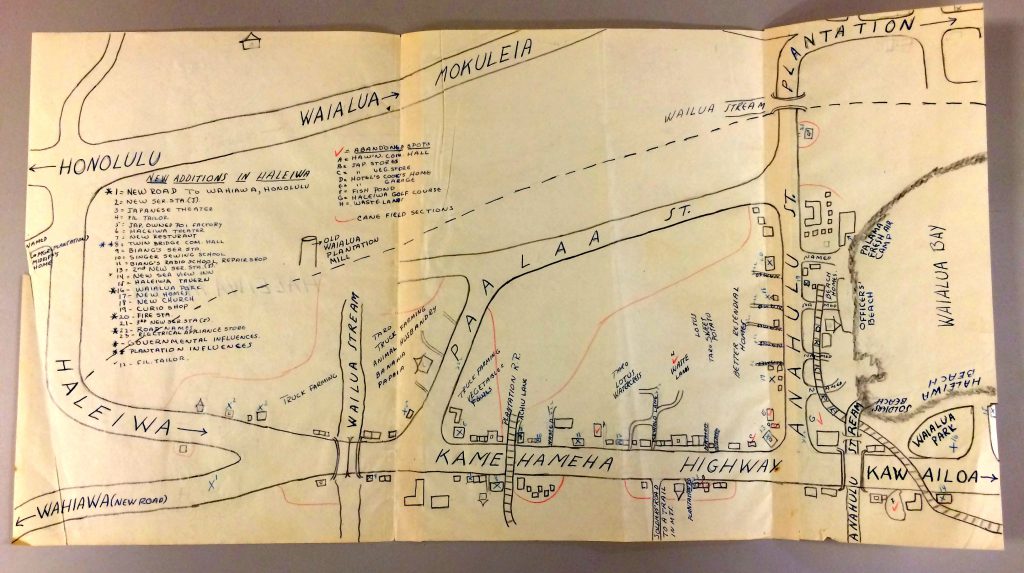

This writer drew two maps of Hale‘iwa, one representing the area as it was in 1930 and the other in 1940, indicated by the insert “new additions of Haleiwa.” These maps roughly approximate the time period covered in N.S.’s rural community study.

The 1930 Map

Starting at mid-point on the left side of the map is Waialua Plantation Manager John Midkiff’s house, brother of the writer’s informant Frank E. The writer includes a key to the area’s churches by denomination; business concerns, which note the ethnicity of the owners; homes; and an intriguing reference to the “Kapukane Club (Haole Spinsters),” which means “no men allowed” and unfortunately can’t be located on the map. Further to the right is the “old Waialua Plantation Mill”; and a list of Hale‘iwa’s medical practitioners, an MD and four dentists, the Japanese practitioners identified only by ethnicity, the others by name, Holt and Chang. Three practitioners are from the “city,” two from the area. Next to this list are names of bridges and at the far right is the plantation.

From left to right on the bottom portion of the map are rice, lotus, vegetable, and taro fields as well as livestock of some sort. Businesses and homes line Kamehameha Highway. About mid-point next to the railroad tracks is “Achiu’s Place” and the “Soldier’s Rd. to a Trail in the Mountains,” which led through Kolekole Pass. Near Waialua Bay, on the right, the writer indicates two schools, Waialua Elementary and the Japanese Language School; Palama Fresh Air Camp; the golf course; beach homes; the Haleiwa Hotel near Anahulu Stream; a fish pond; and beaches that have been leased by the US Army.

The 1940 Map

The writer has organized her map with a key for “new additions,” with no explanation of the asterisks. Item 12 is not listed but is shown on the map on Kamehameha Highway near Kewalo Lane. At mid top of the map are places she calls “abandoned,” which include what she called “Jap stores.” E.L. uses a variant spelling of Waialua – Wailua – for the stream. At the right on the map are “better” homes and several streets.

The Writer, E.L.

Although “not a native resident” of Hale‘iwa, the writer says she chose this community because she spent summers there and became “intimately acquainted with the people.” We also aren’t sure of the writer’s ethnicity; her surname could be Chinese or English. In the 1941 Ka Palapala there is a Chinese (or Chinese Hawaiian?) E.C.H.L. who was a social science major, member of the YWCA, the Sociology Club, and the W.A.A., the Women’s Athletic Association. No other student with the same first and surname appears in Ka Palapala from the early to mid-1940s. We are left to wonder who she was and how she came to know Frank E. Midkiff , one of the organizers of Hawaii’s first community organization, Waialua Community Association, and an informant for her study of Hale‘iwa.

E.L’s Paper

E.L.’s paper offers a comparison of Hale‘iwa to Madison, Wisconsin. She doesn’t explain why she did this, but perhaps she wanted to give her community study more heft, perhaps she just wanted to demonstrate that she was from away or had traveled and was familiar with a community on the continent. This exhibit is concerned only with her discussion of Hale‘iwa.

This writer briefly explores the deeper history of Hale’iwa, referring to the Life of Keoua (1920) by Elizabeth Kekaikuihala Kekaʻaniauokalani Kalaninuiohilaukapu Laʻanui Pratt, great grandniece of Kamehameha I and daughter of Gideon La‘anui. (The published title of this account was History of Keoua Kalanikupuapa-i-Kalani-nui, Father of Hawaii Kings, and His Descendants, with notes on Kamehameha I, First King of All Hawaii.) She mentions the Lili‘uokalani Protestant Church (item “e” on the 1930 map) where the missionary J.S. Emerson and wife are buried, Queen Lili‘uokalani’s summer home, the Waialua Female Seminary, and the Haleiwa Hotel.

Haleiwa is proud to boast that it has the only hotel in leeward Oahu. After B. F. Dillingham laid his first railroad, he visioned a temporary resting spot for tourists traveling by rail or touring the island by buggies or on horseback. In 1899, his visions were materialized with the grand opening of the Haleiwa Hotel on the sloping verdant banks of the Anahulu Stream. … Tourists … partook of the hotel’s genuine hospitality; its famous duck suppers; played on its now abandoned golf course; sailed or fished on the Anahulu Stream; shot ducks and plovers at he hotel’s own duck ponds; hunted pheasants, wild pigs, and goats at its hunting lodge, Puukapu, near Waimea Valley; photographed its lovely grounds of coconut, hau, and hala groves; or crossed the stream on its quaint and unique bridge of curved tree boughs with a resting station in the center to swim and splash in the cool and delightful waters of lovely Haleiwa Beach.

The writer mentions that near the Hotel a Mr. Jenkins once offered glass bottom boat rides, and, as one would expect, Hawaiian boys were at the ready to dive for coins. But with the Depression, the hotel business slumped. In 1935, it was re-invented as an exclusive beach club with most of its members from Schofield Barracks. In 1939, it once again became a hotel but closed permanently in 1943.

Schofield Barracks Vol II 2Jan40 USAMH — Provided by the U.S. Army, U.S. Army Museum of Hawaii, Ft. DeRussy

E.L only mentions the US Army presence in passing:

Haleiwa is a popular resort to the army personnel at Schofield Barracks.. . . The federal government has assigned certain parts as Officers’ Beach and another part for the enlisted men. . . .

To E.L., the Army represented another type of tourist, but for N.S. and her informants, they were a hated occupying force that displaced local residents.

E.L. discusses prominent Hawaiian families in Hale‘iwa. These may be the families N.S. referred to (anonymously) in her paper:

The Awai children are well known in the educational, music, and civic fields of the community. A number of the Achiu boys and grandchildren are working in the district courthouse and other good positions in the city. The Woodd children have brought home to Haleiwa the bacon in the athletics and entertainment fields. Johnny and Jenny [Jennie] Woodd, under the guidance of their father, used to practice swimming on the Anahulu Stream and later became recognized swimmers of Hawaii. Both held amateur titles at one time. . . Jenny and her younger sister, Lillian, are with Ray Kinney and his Hawaiian entertainers. The versatile abilities of Jenny resulted in the composition of several Hawaiian songs, the most famous one describes her beautiful birthplace, entitled, “Haleiwa.”

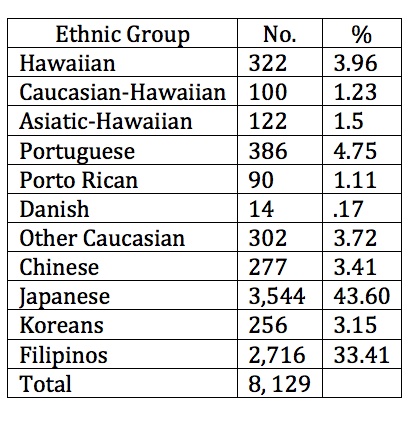

Considering Hale‘iwa’s immigrant groups, the writer offers the standard succession history from the first arrivals, the Chinese to the most recent Filipinos. She seems to have had little or no contact with members of immigrant groups and likely is sharing what she learned in her sociology course or read in Thrum’s Annual, another of her sources. However, she does include the following information from the 1930 census, which reflect the racial categories used at that time:

She points out that 64.09 percent of the population is male, a nearly three-to-one ratio of men to women. As is our custom, we treat all Hawaiians as one group. When added together, Hawaiians number 544 or 6.69 percent, making them Hale‘iwa’s third largest group after the Japanese and Filipinos.

She points out that 64.09 percent of the population is male, a nearly three-to-one ratio of men to women. As is our custom, we treat all Hawaiians as one group. When added together, Hawaiians number 544 or 6.69 percent, making them Hale‘iwa’s third largest group after the Japanese and Filipinos.

E.L.’s conclusion is much the same as N.S.’s:

Materially, [Hale‘iwa] is flourishing with improved and shorter paved roads to Honolulu and other parts, with street names, and improved transportation and recreational facilities. I dare not make the attempt to conclude that [the village] is on the go economically even with the hotel regaining its status and a small number of stores popping up. Unless there are other attractive vocational opportunities outside of the plantation, the population will continue to be stable and after awhile, will probably decline instead of increasing, in spite of new material improvements by the government and the stretching octopus tentacles of the plantation.

RASRL Context

A RASRL writer’s view of a community was framed – focused and delimited – by her ethnicity, socio-economic class, and her own direct experiences. In turn, these factors determined her sources, clearly illustrated by the two writers featured here. N.S. relied on members of the Japanese community, likely shop owners, who still remained in Hale‘iwa and her own vivid childhood memories. E.L. had access to Midkiff, a member of the Haole elite and, to what extent it isn’t clear, memories from summer visits. To expand her study E.L. consulted written sources, such as Thrum’s Annual and Pratt’s biography of La‘anui and drew from official sources, such as the census and voting records.

We are offered two views of Hale‘iwa that are similar in factual data but quite different in the writers’ sense of the history of the place. It isn’t unusual for an outsider or visitor – and E.L. seems to be more this than not – to focus on a history of Hawaiians and a recounting of subsequent settlers, while a first-generation American student’s view is highly personal with a foreshortened history, often extending no further back than to the arrival of her ethnic group to the area. In tone, N.S.’s narrative could be an early example of the “small kid time” genre in local literature.

Social Historical Context

These two papers and maps draw our attention to Hale‘iwa’s role in Hawaii’s major industries. Studies of plantations are abundant in the RASRL archive and although Waialua Plantation is important here, it is mostly viewed from a distance with Hale‘iwa as the central focus. Hale‘iwa – like Ōla‘a on Hawai‘i and Kukui‘ula on Kaua‘i, also part of this exhibit – was a village with a mutually dependent relationship with the plantation. Both writers refer to changes made by Waialua Plantation that affected Hale‘iwa’s businesses and population. Family owned stores began to close once the Plantation store began stocking goods that only the small shops previously had offered. The expansion of education beyond the eighth grade level, intended to keep families rooted in the area, provided the preparation and confidence young adults needed to continue their education at the University or to seek jobs in Honolulu.

Even tourism, a topic rarely examined by RASRL writers, makes an appearance in these papers, both of which mention attractions that drew visitors to the area. Tourism was a sign of the area’s economic maturity and had the potential to offer revenue and jobs, but for local residents like N.S. it’s not clear whether the sacrifice was worth it.

But the most dramatic impact on the community is the presence of the military in Hale‘iwa. The Army Corps of Engineers’ dredged Anahulu Stream to help with flood control, but also to create a landing from which to launch crash boats, which were used to rescue planes that had gone down at sea.

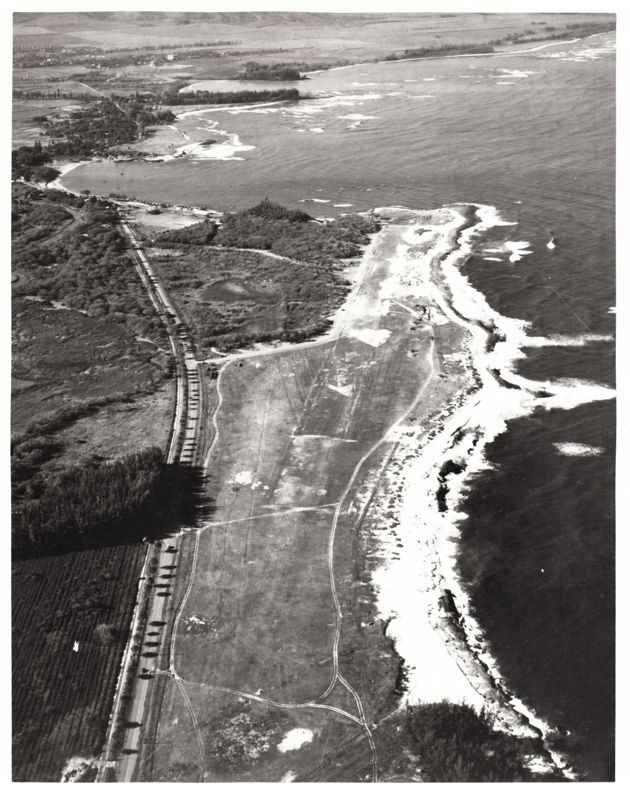

Haleiwa airfield USAMH 2621 1943 — Provided by the U.S. Army, U.S. Army Museum of Hawaii, Ft. DeRussy

In 1933 the military operated Haleiwa Airfield. And, as our mapmakers noted, the Army claimed what had been civilian beaches for its own use.

Beyond the frame of the maps is the powerful force and presence of Schofield Barracks:

Schofield Barracks, the second largest city on Oahu, had better entertainment facilities than those provided to the citizens of many contemporary cities. In February 1920, for example, Schofield offered 27 movies to 4,330 attendees, hosted informal athletics for 5,265 soldiers, conducted 270 education classes for 3,780 students, and held 13 religious meetings of 2,325 attendees. … The Kaala Club, completed in 1921, was reputed to be the best enlisted men’s club in the army, with six movie theaters, weekly dances, pool tables, roller skating, a library, and a large recreation room. Schofield boasted a post exchange, which in 1929 conducted $1 million in business and provided meat, dairy and vegetable markets, a filling station, a beauty parlor, a jeweler, and a dozen restaurants. In 1930, Schofield expanded its recreation center to include a gymnasium, a 1,700-seat theater, a 10,000 seat “Boxing Bowl,” a swimming pool, athletic fields, and a library. After the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, soldiers could go to their regimental beer garden or walk off post to Hasebes or Kemoo Farms for food and drink. … With an eye to keeping soldiers out of brothels and bars, the army provided healthy and wholesome off-duty entertainment. In the 1920s Schofield leased Haleiwa Beach on Oahu’s North Shore; any soldier who could scrape up the twenty-cent round-trip bus fare could spend the weekend swimming, hiking, playing sports, or sleeping (Brian McAllister Linn, Guardians of Empire: The U.S. Army and the Pacific, 1902 – 1940, 1997, pp. 119-20).

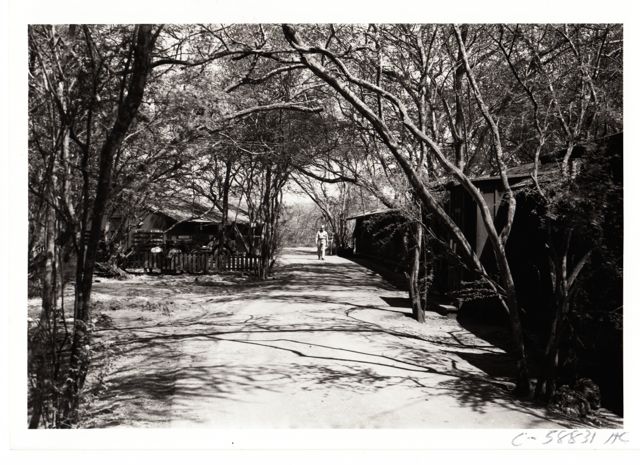

Haleiwa Airfield barracks and street scene USAMH 2554 1943-44 — Provided by the U.S. Army, U.S. Army Museum of Hawaii, Ft. DeRussy

The Army’s encroachment on Hale‘iwa continued throughout the war. The Director of Palama Settlement, Philip S. Platt, was dismayed to find that the Army had occupied the site of Fresh Air Camp. In a letter to Lt. Col. Ackerson of the Inspectors General Department, dated January 19, 1942, Platt’s surprise was evident:

Palama Settlement, a charitable organization dependent upon private contributions, maintains a vacation camp at Waialua in an area considered now, I believe, a military reservation. . . . the 21st Infantry and the 52nd Field Artillery . . . have occupied the cabins and are using the toilets, showers and clothes washing facilities, pavilion, etc. This occupation occurred without requesting permission, which would have been granted had it been asked.

Of course, permission, retroactively and immediately, was granted, but this meant that the Settlement would no longer receive income – $1,400 annually – that the camp was generating, since “civilians do not wish to occupy these buildings in view of the presence of soldiers and the presence of numerous military emplacements.” This loss of income didn’t mean that Palama’s rent, taxes, and insurance expenses stopped. While Platt concluded his letter by stating that the Settlement was eager to assist the Army and improve morale, nonetheless, he noted “that the contributing public should not be required to meet the expenses which are unavoidable under the present circumstances” (Palama Settlement Archive, Box 46, Folder 02).

No one at the time could have anticipated the transformation of Hale‘iwa from a sleepy plantation town to a tourist attraction complete with boutiques, the world’s most famous shave ice stand, and surf shops. He‘e nalu was transformed into the international sport of big wave surfing. And the US Army’s subtle but inexorable land grab would grow from a section of the beach reserved for the recreation of GIs to the largest base in Hawai‘i.